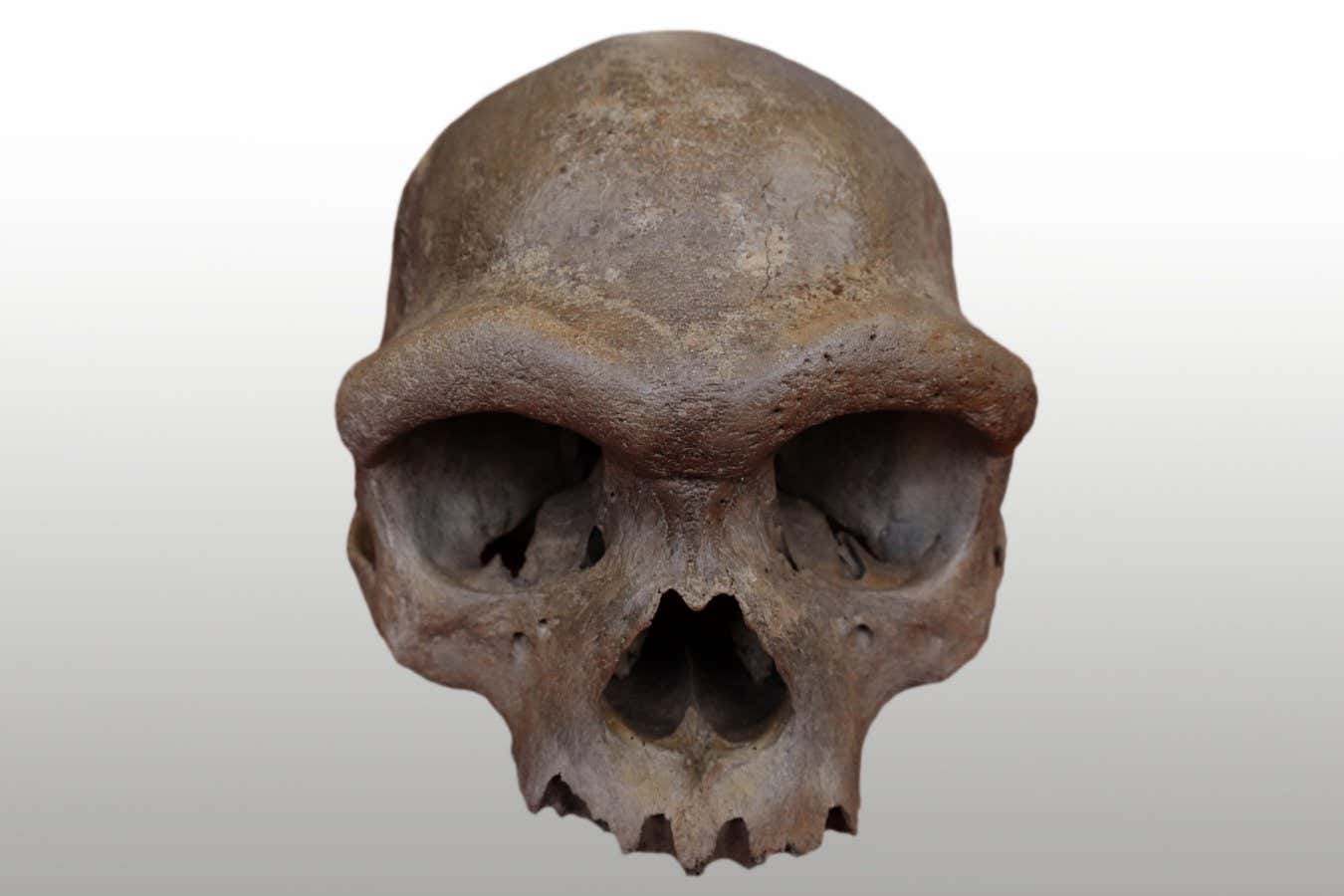

A skull from China has been identified as Denisovan using molecular evidence – so ancient humans once known solely from their DNA finally have a face

Hominin cranium from Harbin, China, now identified as a DenisovanHebei GEO University

Hominin cranium from Harbin, China, now identified as a Denisovan

TheDenisovans, a mysterious group of ancient humans originally identified purely from DNA, finally have a face.

Using molecular evidence,Qiaomei Fuat the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing and her colleagues have confirmed what many researchers suspected: that a skull from China known as “dragon man” belonged to a Denisovan.

Read moreThe other humans: The emerging story of the mysterious Denisovans

The other humans: The emerging story of the mysterious Denisovans

This fits with other evidence suggesting that the Denisovans were large and stocky. “I think we’re looking at individuals that are all [around] 100 kilos [of] lean body mass: enormous, enormous individuals,” saysBence Violaat the University of Toronto in Canada, who was not involved in the study.

The Denisovans were first identified in 2010. In Denisova cave in the Altai mountains of Siberia, researchers found a sliver of finger bone from an unidentified ancient human. Preserved DNA revealed that it wasn’t a modern human (Homo sapiens), nor a Neanderthal (Homo neanderthalensis), butsomething hitherto unknown.

Genetic evidence also revealed thatDenisovans had interbred with modern humans. Today, populations in South-East Asia and Melanesia carry up to 5 per centDenisovan DNA,which implies that Denisovans were once widespread in Asia.

Keep up with advances in archaeology and evolution with our subscriber-only, monthly newsletter.

After these discoveries, researchers began looking for Denisovan fossils, both in the field and in museum collections.Several have been found, notablya lower jawbonefrom Baishiya Karst cave on the Tibetan plateau, which was confirmed using proteins from the fossil andDNA from surrounding sediments. In April,a jawbone dredged from the Penghu Channeloff the coast of Taiwan was confirmed to be Denisovan, based on preserved proteins.

However, there was still a frustrating disconnect. The fossils confirmed as Denisovans using molecular evidence were all small, so they weren’t very informative. Meanwhile, there were manymore complete fossilsfrom Asia that weresuspected to be Denisovan, butnone had yielded molecular evidence.

Fu and her colleagues set out to obtain preserved DNA or protein from a hominin cranium found in Harbin in north-east China. First described in 2021 after having been kept secret for decades, the cranium is unusually large and bulky, with thick brow ridges and capacity for a brain of a similar size to ours.It was namedHomo longi– or dragon man – by its discoverers.

“My impression was, this is the right kind of thing in the right place at the right time to be a Denisovan,” says Viola.

Fu says it was extremely difficult to get preserved molecules from the Harbin cranium. Her team’s attempts to obtain DNA from the bone proved fruitless. However, they did manage to get 95 proteins, which included three variants that are unique to Denisovans.

Feeling that this wasn’t enough to be certain, Fu began testing dental calculus, the hard plaque that forms on teeth. This yielded mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited from the mother. It was a “tiny amount”, she says, but enough to confirm that the remains were Denisovan.

“That’s an incredible result, and fantastic that they even tried,” saysSamantha Brownat the National Research Center for Human Evolution in Burgos, Spain. “I think most researchers would overlook dental calculus for genetic studies.”

Read moreSurvival of the friendliest? Why Homo sapiens outlived other humans

Survival of the friendliest? Why Homo sapiens outlived other humans

Now that the bulky Harbin skull has been identified as Denisovan, it confirms something long suspected: Denisovans were big.

“There were clues [to] that right from the beginning with their teeth,” says Brown: the handful of molars that were found were unusually large. Known jawbones were also big. “We thought Neanderthals were the stocky ancestor, but actually it might be Denisovans that really were the big boys of the palaeontological record.”

It isn’t clear why this was the case. Neanderthals’ size and build have been linked to the cold climates in Europe and western Asia where they lived. Some Denisovan sites, including Denisova cave and the Tibetan plateau, were also cold – but others were tropical. “I think we’ll have to think about what this really means,” says Viola.

It may be that the Denisovans changed over time. Fragments from Denisova cave reveal two groups: one from 217,000 to 106,000 years ago, and the other from 84,000 to 52,000 years ago. The Harbin cranium is at least 146,000 years old, and Fu found that its proteins and mitochondrial DNA matched the older group. But we don’t have confirmed large fossils of the more recent Denisovans, so we don’t know what they were like.

“There’s just lots of different groups of these guys who are moving around the landscape, kind of independently, that are often separated from each other for probably tens of thousands of years,” says Viola. We shouldn’t expect them to all look alike, he says.

Journal reference:CellDOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.05.040

CellDOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.05.040

Journal reference:ScienceDOI: 10.1126/science.adu9677

ScienceDOI: 10.1126/science.adu9677

Receive a weekly dose of discovery in your inbox!

We'll also keep you up to date withNew Scientistevents and special offers.