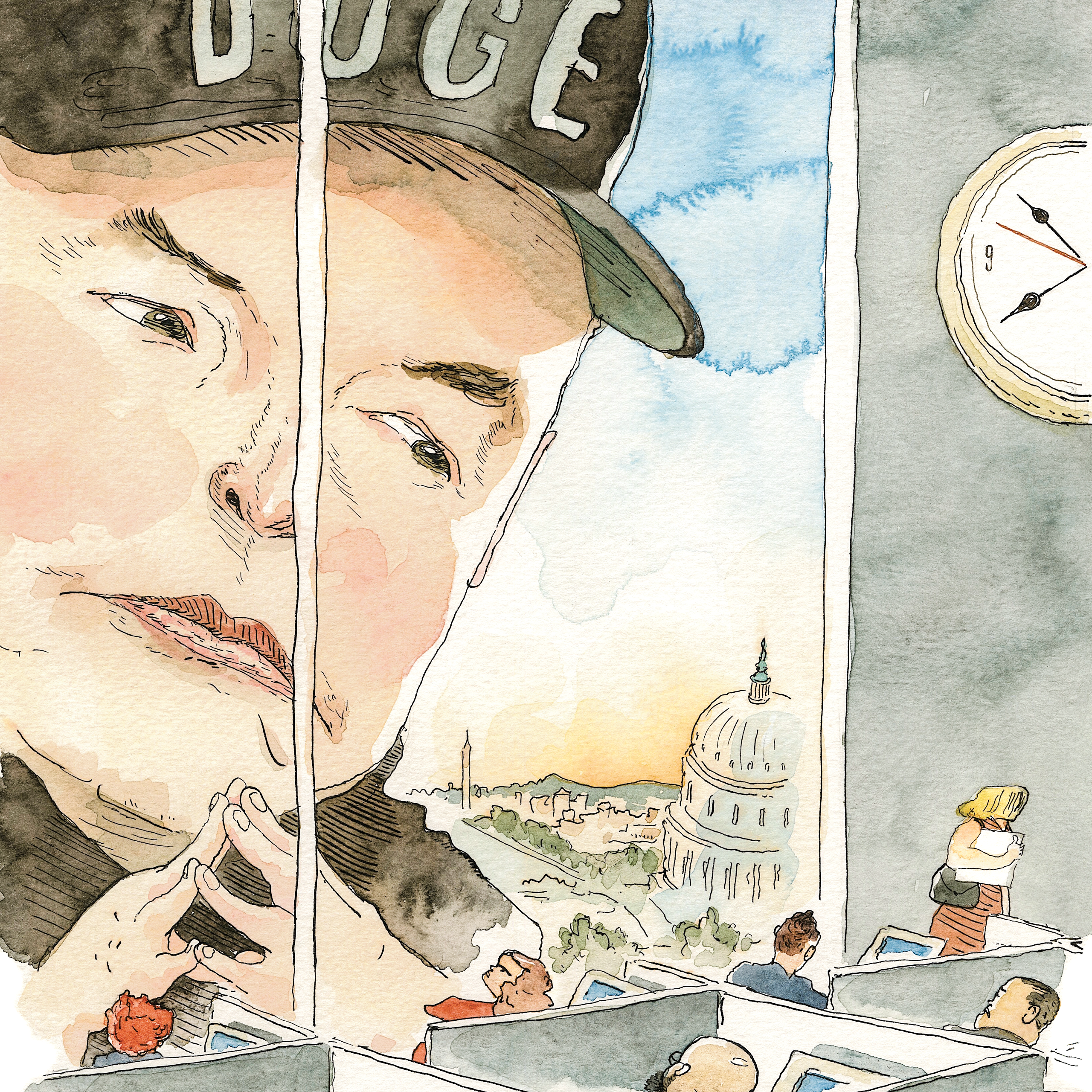

On March 27th, Sahil Lavingia walked into the Secretary of War Suite, in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, to attend an all-hands meeting of the Department of Government Efficiency. Lavingia had been aDOGEemployee for two weeks, part of a small team embedded at the Department of Veterans Affairs. So far, it had been an unexpectedly isolating experience. Lavingia communicated over the messaging app Signal with another member of the V.A.’sDOGEteam, but there didn’t seem to be a Signal channel where he could interact with the rest ofDOGE. Instead, Lavingia would watch Elon Musk, who led the initiative, engage with his allies on X. Lavingia told me, “You’d see where the dolphins were swimming—like, now we’re looking at D.E.I. contracts—and so you’d swim there, too.”

Before coming to Washington, Lavingia lived in New York, where he worked at Gumroad, an e-commerce site that he’d founded more than a decade earlier. He wasn’t really aMAGAguy, but he had always thought it would be interesting to work in government, and he admired Musk. In October, at a tech meetup at the New York offices of the venture-capital firm Andreessen Horowitz, Lavingia talked with someone who later introduced him to aDOGEstaffer. The staffer put him in touch with aDOGEengineer, who connected him with aDOGErecruiter. The calls didn’t last much longer than five minutes. “All the questions were about ‘When can you move to D.C.?’ ” Lavingia said. Eventually, Lavingia told me, he talked to Steve Davis, the president of Musk’s Boring Company, who asked if Lavingia could code. Yes, Lavingia said. A few weeks later, he got a text: a job had opened up at the V.A. “I felt like, O.K., finally, that’s some information,” Lavingia said. He started in mid-March, making an hourly wage of about thirteen dollars.

President Donald Trump formally createdDOGEby executive order on his first day in office, rebranding what had been the United States Digital Service, a kind of internal tech consultancy for the federal government. Musk’s allies quickly staffed it: Davis, who had helped Musk overhaul Twitter, effectively became C.O.O., and Chris Young, a Republican political operative who had led Musk’s superPAC, became a senior adviser. On February 2nd,Wiredidentified six young computer engineers, all in their late teens or early twenties, who were working forDOGE. The young coders, collectively dubbed the “DOGEkids,” had set up shop at the Office of Personnel Management and at the General Services Administration, where, according toPolitico, some of them appeared to be living, having furnished four rooms withIKEAbeds. That cinched the cultural image.DOGEwas the tech industry’s outpost in government, the department that would move fast and break things.

Initially, it was hard to know how seriously to take the new venture, whose name derived from a meme coin. A senior figure at a conservative think tank predicted to me thatDOGEwould yield nothing more than a government report that would get stuffed away in a drawer. ButDOGEstaffers were soon identifying contracts to cancel and employees to let go. On January 28th, the Office of Personnel Management sent most federal employees an e-mail titled “Fork in the Road,” which warned of involuntary downsizing to come and offered them the chance to resign with eight months of pay and benefits. (Musk had sent Twitter employees an e-mail with nearly the same subject shortly after he bought the social-media company, which he rebranded as X.) Those who stayed in their jobs were soon required to document, at the end of each week, five things that they had worked on. A series of lawsuits accumulated inDOGE’s wake, but its actions seemed to be producing results. At the end of March, theTimesestimated that the federal government had potentially been cut by twelve per cent.

Lavingia and other members of theDOGEteam at the V.A. had prepared a list of accomplishments to present at the all-hands meeting. There were about fifty people in the room at the Secretary of War Suite, a surprisingly small number, Lavingia thought, if this was all ofDOGE. When Musk walked in, he asked attendees to share their recent victories, and pontificated about how broken the government was. “It was this very surreal scene,” Lavingia said. He tried to engage Musk in a conversation about a project, but “everyone looked at me like I was weird, like, ‘Why are you trying to get feedback from your boss?’ ” At one point, someone asked how many I.T. workers there were at the I.R.S. It turned out to be more than seven thousand. (The agency has a total of around a hundred thousand employees.) A member ofDOGE’s I.R.S. team said that he thought the tax agency needed an “exorcist.” “Elon was, like, ‘Wait, seriously?’ ” Lavingia recalled. After a few hours, Lavingia left, disappointed. “It’s almost like this is one of the things you get for working atDOGE,” he said. “You get to hang out with Elon once in a while.”

Lavingia had already grown skeptical of the effort. At the V.A., he’d initially planned to update what he’d been told was an outmoded and fragmented human-resources system, but it seemed to be working just fine. “DOGEnever had an information flow that was, like, ‘Hey, Elon wants us to do this,’ ” Lavingia said. “You’re asked to give a lot, but you don’t get any access to information.” In April, he returned to New York, working remotely on improving the V.A.’s internal chatbot, VA GPT. In early May, he gave an interview that was published inFast Company, in which he said of the government, “It’s not as inefficient as I was expecting, to be honest. I was hoping for more easy wins.” Not long after that, his access to the V.A. systems was cut off; he was fired.

Later that month, Musk announced that he, too, was leavingDOGE, after a run in which he had impressively stretched the definition of what a “special adviser” to the President could do. In Trump’s White House, with its long red ties and compulsory praise circles, Musk wore novelty T-shirts and baseball caps, and attended meetings with his four-year old son, X, whom Trump pronounced “a high-I.Q. individual.” He installed a Starlink satellite system on the White House roof, and sold Trump a red Tesla on the White House lawn. Trump obligingly climbed into the driver’s seat and assessed the car’s interior. “Everything’s computer,” the President observed.

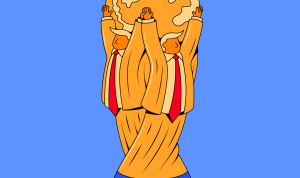

At Musk’s sendoff in the Oval Office, Trump presented him with an oversized White House key and said that his work onDOGEhad “been without comparison in modern history.” But the relationship between the two men, always transactional, had turned into a bad deal for both of them. DOGE had achieved far fewer savings than Musk had anticipated, leaving Trump backing a budget bill that would add trillions to the deficit. Musk’s work for Trump, meanwhile, had alienated liberals and centrists, tanking Tesla’s sales and stock price. In the Oval Office, Musk had a black eye, which he said he’d got after his son hit him in the face. A reporter asked him about a recentTimesstory alleging that he had used ketamine and other drugs extensively on the campaign trail. Musk said, “Let’s move on.”

Within days, Trump announced that he was withdrawing the nomination of Jared Isaacman, Musk’s business associate, to runNASA, after “a thorough review of prior associations.” Musk called the Republican budget bill a “disgusting abomination,” and later started a poll on X asking if it was time to start a new political party. Trump seemed to take this personally, posting that the easiest way to save money in his budget bill would be to “terminate” the “Billions and Billions of Dollars” in government subsidies that Musk’s companies received. “Elon was ‘wearing thin,’ ” the President wrote. “I asked him to leave, I took away his EV Mandate that forced everyone to buy Electric Cars that nobody else wanted (that he knew for months I was going to do!), and he just went CRAZY!” Musk responded, “Such an obvious lie. So sad.”

For a few hours on June 5th, the President and the world’s richest man went back and forth, until the fight landed on the subject of many rabid internet disputes—the convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. “Time to drop the really big bomb,” Musk wrote. “@realDonaldTrump is in the Epstein files. That is the real reason they have not been made public. Have a nice day, DJT!” (Trump addressed the claim, telling NBC that he was “not at all friendly” with Epstein.)

At that point, many of the most experienced and talented government workers had left their jobs. Those who remained were often forced to pare back the mission and the scope of their work. Jacob Leibenluft, a senior Biden official, told me, “WhatDOGEhas done, what the Administration has done, is cause a remarkable exodus of talent—of people who have built years and years of knowledge that is critical to the government functioning and who would, under normal circumstances, pass that knowledge on to the next generation of civil servants.”

Lavingia thought that the rupture between Musk and Trump had probably marooned many of the remainingDOGEemployees, too, some of whom are still embedded in agencies throughout the federal government. It was also possible, Lavingia told me, thatDOGE’s strength and its weakness had the same source. He’d seen from the inside thatDOGEhad no real internal structure. “At the end of the day,” he said, “DOGEis just Elon.”

Dawn on the Potomac River: rowers, joggers, a quickening column of jets descending toward the runways at Reagan National. Culs-de-sac empty; park-and-ride lots fill; the Beltway clogs hellishly. The federal government is everywhere. It is downtown, in the marble buildings near the White House, a sort of nineteenth-century visual trick to lend the appearance of Greco-Roman permanence to what remains a somewhat tenuous political project. But it is also in the Baltimore suburb of Woodlawn, where ten thousand people work at the Social Security Administration’s headquarters; on the brick campus of the National Institutes of Health, in Bethesda; and in the sprawl of the defense contractors out toward Dulles. This is not the political D.C., but the projects are vast. I recently asked a former senior official at the S.S.A. if she’d been worried when Trump won. “Not really,” she said. “My focus was on the solvency crisis.”

Conservatives tend to inveigh against the federal apparatus in Washington; liberals mostly defend it. But the operations of government reflect both Republican and Democratic ambitions. Paul Light, a scholar of public service at N.Y.U.’s Wagner School, has estimated that federal contractors outnumber civil servants by two to one. Elaine Kamarck, of the Brookings Institution, has found that the majority of federal employees now work in security-related fields—thirty-six per cent of them at the Department of Defense alone. For the most part, the U.S. government is organized not to pursue transformative change but to create systems of accountability, and the growth of its expenditures is mostly tied to the sheer scale of what it is keeping tabs on. Federal spending has quintupled since the mid-sixties, adjusting for inflation, to about seven trillion dollars a year. The number of federal workers has basically stayed flat.

People cheat the federal government all the time, in all kinds of ways. Waste exists at every level. In 2011, Boeing was found to have been grossly overcharging the Army for spare helicopter parts; a four-cent metal pin, for example, was billed at $71.01. In 2020, Harvard returned $1.3 million to the Department of Health and Human Services after a public-health professor allegedly overstated how much time she’d spent working on an overseasAIDS-relief grant. Jetson Leder-Luis, a professor at Boston University who studies health-care fraud, told me that, within Medicare and Medicaid, “you get everything from doctors reclassifying procedures to, like, organized crime.”

Leder-Luis likes to cite a study that he and some colleagues conducted on fraudulent billing for dialysis transportation. Medicare has long reimbursed patients too sick to get to dialysis on their own for the cost of ambulance rides. But some unscrupulous actors (Leder-Luis thinks they were mobsters in Philadelphia) realized that it was possible to pay kickbacks to relatively healthy dialysis patients for ambulance rides they didn’t need. Word spread; between 2003 and 2017, Leder-Luis and his colleagues estimated, Medicare spent around five billion dollars on fraudulent ambulance rides. “The F.B.I. has videos of some patients walking in and out of ambulances,” Leder-Luis told me. Dialysis costs make up roughly one per cent of the federal budget. If there was that much fraud in dialysis transportation, Leder-Luis said, imagine how much there is across the entire public sector.

In recent years, wonks in both parties have begun to focus on government inefficiency as a problem. On the center left, the so-called abundance movement calls for a thinning of regulation, to allow the country to more easily create housing and clean energy. On the Trumpist right, the prevailing view is that the government has been overtaken by left-wing ideologues and the only solution is to clear-cut the bureaucracy. Trump spent the campaign promising to purge the federal government of wokeism; his advisers were committed enemies of foreign aid, consumer protection, and the Department of Education. Project 2025, a nine-hundred-page playbook for a conservative President to “dismantle the administrative state,” called the independence of the bureaucracy an “unconstitutional fairy tale.”

The last major campaign to remake the Washington bureaucracy was championed by Vice-President Al Gore, during the Clinton Administration, and developed under the name Reinventing Government. The idea was to bring the public sector up to date with the internet. Kamarck, of the Brookings Institution, was its lead staff member. She leveraged the government’s own expertise: teams of civil servants from other departments were embedded with each agency to streamline and improve its processes. Eventually, the Clinton White House got Congress to pass more than eighty separate laws related to the Reinventing Government initiative. “If you want these changes to be permanent,” Kamarck told me, “the only way to do it is to get them in law.”

DOGEwas conceived in something like the opposite fashion. In the spring of 2023, Vivek Ramaswamy, a biotech entrepreneur who had recently launched a bid for the Republican Presidential nomination, invited a New York lawyer named Philip Howard to meet with him at his campaign headquarters in Columbus, Ohio. Since the nineties, Howard has been a guru for business leaders interested in civil-service reform. Ramaswamy wanted to test out some ideas for remaking the federal bureaucracy. As the meeting progressed, Howard had the sense of an “over-intelligent mind spinning into some new theory that creates a new reality that’s not actually connected to reality.” At one point, he recalled, “Vivek was saying, ‘I think the President can really shut down agencies.’ I said, ‘You know, Congress establishes an agency. Do you really think the President can just . . .’ And he said, ‘Oh, yes, yes, it’s fine.’ ” Howard later told one of Ramaswamy’s advisers, “I really don’t think Vivek should go public with this, because it’s just not credible.”

A week after the election, Trump announced in a formal statement that “the Great Elon Musk, working in conjunction with American Patriot Vivek Ramaswamy, will lead the Department of Government Efficiency.” Initially, the two co-chairs seemed poised to occupy separate spheres. Ramaswamy would spearhead a deregulation effort; Musk would focus on cost cutting. In a joint op-ed in theWall Street Journal, they said that they would work closely with the Office of Management and Budget, which is often described as the federal government’s central nervous system. Before the election, Ramaswamy suggested in an interview that the White House could simply fire all nonpolitical appointees whose Social Security numbers began with an even digit or ended with an odd digit. “Boom, that’s a seventy-five-per-cent reduction,” he said. A month later, Musk was asked how much moneyDOGEmight save taxpayers. “I think we can do at least two trillion,” he said.

But during the transition Ramaswamy and Musk increasingly disagreed about how to make the government more efficient. Ramaswamy, who had apparently come around to the fact that significant cuts would require an act of Congress, began meeting regularly with a small group of legislators. Musk mostly did not attend. A source close toDOGEtold me that Musk seemed to regard members of Congress as irrelevant, sometimes referring to them as “N.P.C.s,”—non-player characters—the often mute and nameless figures who populate the backgrounds of video games.

Musk was more interested in cutting spending via the executive branch, and spoke often, according to the source close toDOGE, of a need to “control the computers.” In meetings, Ramaswamy resorted to using metaphors from the tech world to emphasize the importance of deregulation, calling the government’s rules “the matrix” and insisting thatDOGEneeded to rewrite its source code. Musk was unmoved.

On the eve of the Inauguration, CBS News quoted a White House insider saying, “Vivek has worn out his welcome.” The following day, Ramaswamy leftDOGE. Musk, in the faintly stuffy office he inherited in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, reportedly installed a large-screen TV, so that he could play video games; he sometimes slept there. A prominent conservative told me that, online, people were devising ways to influence Musk’s efforts. “You do it by tweeting at Elon and sucking up to him,” he said. “He’s like a prism, and all of social media kind of feeds to him through X.” The trouble, he said, was that “Elon goes on these destiny quests, sometimes looking for something that isn’t there, and then a lot of the government is on a destiny quest.”

Danny Werfel spent much of his career in the federal government. He worked as a policy analyst in the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, as a trial attorney in the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, and as controller at the Office of Management and Budget. Most recently, as Biden’s commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service, he was given the rare opportunity to not only run the government but also change it. Congress had pledged eighty billion dollars over ten years to modernize the I.R.S. and bring its collection of taxes up to par with the efforts to evade them. Werfel had expanded the agency’s Large Business and International Division, its enforcement efforts targeting cryptocurrency and high-net-worth individuals, and its investments in artificial intelligence and other technologies. As late as December, 2024, he was still hiring the next generation of civil servants. At the I.R.S.’s annual holiday party, employees were invited to have their photo taken with him; one young man, after the camera clicked, said, “Thank you, Coach!” He was a new hire, right out of college. A decade earlier, he and Werfel’s son had played in the same northern-Virginia Little League. His father, it turned out, also worked at the I.R.S.

After Trump won, Werfel “wasn’t a hundred per cent sure” that the new Administration would continue the I.R.S.’s modernization efforts, but he tried to engage with it in good faith. In early January, representatives from Trump’s transition team andDOGEmet with I.R.S. leaders over Zoom to discuss the handover of power. Werfel’s team had rehearsed the scenario, fine-tuning the language that they planned to use. “We said, ‘Look, we know you have a remit for shrinking government from a people standpoint,’ ” Werfel recalled. “ ‘Do we have that right?’ And they didn’t argue—they agreed. We said, ‘Wouldn’t it be great if you could do that and also improve or maintain the performance of the I.R.S., and its collections?’ And it was, like, ‘O.K., we’re listening.’ ”

Werfel promised the Trump officials that, with a little patience, the I.R.S. could employ fewer federal workers and bring in more revenue. The more effective tax regime that Werfel had been building was not just funded; it was half assembled, like the Death Star. He urged the Administration to give it time to become fully operational. “Think of it as spans across a stream,” Werfel said. “Some of the spans are complete, and you can drive across and automate. Some of them are only halfway complete, so you can’t drive until you finish the span, and some of them you need to build before you begin.” Werfel proposed that the Trump Administration commit to reducing the agency’s personnel in the course of two to four years, and that it “modernize strategically,” to insure that fewer people didn’t mean less revenue or worse service. “That was our pitch,” Werfel said. “It resonated in the moment.”

Hours after being sworn in, Trump signed twenty-six executive orders, restoring the federal death penalty, withdrawing the U.S. from the World Health Organization, placing a ninety-day pause on foreign aid, and eliminating diversity-equity-and-inclusion programs across the federal government. The executive order establishingDOGEseemed, by comparison, to describe a humble purpose: “to implement the President’s DOGE Agenda, by modernizing Federal technology and software to maximize governmental efficiency and productivity.” Musk, though a frequent presence in the West Wing, was technically an unpaid adviser.

One area of focus for both Musk and the Administration was eradicating what the Tesla founder called the “woke mind virus.”DOGEsoon boasted of cutting more than a billion dollars in D.E.I. contracts. But what, exactly, qualified as a D.E.I. program was open to interpretation. At Social Security headquarters, civil servants were directed to scrub mentions of “diversity” and “equity” from grants, publications, and performance evaluations. Laura Haltzel, who was the associate commissioner for the Office of Research, Evaluation, and Statistics, told me, “It was, like, ‘O.K., this is incredibly inefficient. But we’ll get through it.’ ”

For twenty-five years, Haltzel’s office had operated a research-and-grant program to study the effects and the viability of the Social Security system. Recently, the program had been awarding points to potential grantees if they partnered with institutions that served minority populations, such as historically Black colleges and universities. Because of this, Haltzel told me, she was ordered to shut down the entire program, a request that she viewed as absurd. The program was not focussed on race or gender. It predated the term “D.E.I.” by decades. Haltzel’s boss had petitioned the Office of Management and Budget not to end the initiative altogether, to no avail. “They said, ‘You’ve got to kill it,’ ” Haltzel said.

Similar changes were under way at the I.R.S., where workers were deleting references to “diversity,” “equity,” and “inclusion” from the service’s employee handbook. A senior I.R.S. official told me, “If you could measure enforcement actions by month, I bet you’d have seen a significant decline in February, because everyone was worrying about what to do about their jobs.” On February 4th, Musk posted a survey on X: “Would you like @DOGE to audit the IRS?” Two weeks later, seven thousand of the agency’s probationary employees—those who’d been hired in the past year or so—were fired. An I.R.S. employee told ProPublica, “It didn’t matter the skill set. If they were under a year, they got cut.” (A federal court later ruled that the firings were unlawful.)

Many of the fired employees had focussed on curbing tax evasion by the country’s wealthiest people. The Yale Budget Lab estimated “very conservatively” that, ifDOGEcut half the I.R.S.’s employees, as it had reportedly considered doing, the reduced workforce would cost the government four hundred billion dollars in lost tax revenue, far more than the savings in salaries. Werfel used the analogy of a backpack: if you are filling a backpack, you start with the thing that is most important to you, and then find room for the rest. “They didn’t start by filling the backpack with efficiency, or collections,” Werfel said. “They filled it with job cuts.”

One evening, his wife wondered what had happened to the Little League player from the Christmas party. It turned out that he had been fired that day; he’d been given an hour to vacate the I.R.S. headquarters. His father had walked him out the door.

Every incoming Administration enjoys an unusual power in its first weeks, since the new Cabinet secretaries have not yet been appointed, and thus cannot yet object to changes at their agencies. The White House’s pause on foreign aid raised a particular panic in the Kinshasa office of the United States Agency for International Development. The following weekend, rebels from the paramilitary group M23 took control of the Congolese city of Goma, part of an ongoing conflict that Congolese citizens had long blamed on Western nations, including the U.S. There were rumors of protests in the capital. Meanwhile, dozens of senior U.S.A.I.D. officials had been placed on administrative leave, scrambling the aid workers’ lines of communication to Washington and clouding the question of who was running the agency.

On the morning of Tuesday, January 28th, many U.S.A.I.D. workers had already sent their children to school on a bus and boarded a shuttle to the U.S. Embassy when they received messages telling them that the situation in the capital might no longer be safe. The vehicles turned around, bringing their passengers back home. According to a senior U.S.A.I.D. official in Kinshasa who filed an affidavit in federal court under the pseudonym Marcus Doe, one U.S.A.I.D. worker reported that protesters were setting fires outside his residence. A little later, he requested an evacuation—his front gate had been breached. On social media, Marcus Doe could see videos of looting, and outside his own home he could hear protesters chanting. He and his wife called their kids inside and locked the doors.

Leaders at the Embassy decided to evacuate the staff, but the executive order pausing foreign assistance had made it harder for U.S.A.I.D. personnel to figure out how to fund their travel. Staffers were losing access to the agency’s internal payment system, and officials in the Congo were reluctant to authorize an expenditure, for fear that they would be accused of circumventing the executive order. Employees sought a waiver from U.S.A.I.D.’s acting administrator, a career official named Jason Gray. It was approved, but only after Marcus Doe and others had started evacuating. “I began to feel an intense sense of panic that my government might fully abandon Americans working for U.S.A.I.D. in Kinshasa,” Marcus Doe recalled. He and his colleagues began coördinating with contacts at other foreign-aid organizations. They made it across the river to Brazzaville by boat that night, with an allotment of one carry-on-size bag per person.

The new deputy administrator of U.S.A.I.D. in Washington was Pete Marocco, a former marine who, during the first Trump term, had left his job at U.S.A.I.D. after subordinates filed a thirteen-page memo accusing him of mismanagement and workplace hostility. In a closed-door meeting with lawmakers in March, the WashingtonPostreported, Marocco called U.S.A.I.D. a “money-laundering scheme” and said that he was examining whether foreign aid was even constitutional. “What we’re seeing right now is Pete’s revenge tour,” a former senior U.S.A.I.D. official recently told NPR. “This is personal.”

Musk shared Marocco’s dim view of foreign assistance. On January 28th, while U.S.A.I.D. staff were fleeing Kinshasa, the White House press secretary, Karoline Leavitt, told reporters thatDOGEand the O.M.B. had discovered that the Biden Administration planned to purchase fifty million dollars’ worth of condoms for Gaza. Musk posted on X, “Tip of iceberg.” In recent years, U.S.A.I.D., in its efforts to combat H.I.V. and AIDS around the world, has earmarked around seventeen million dollars annually for condoms, including allocations to the province of Gaza in Mozambique; none of the money went to the Palestinian territories. “Some of the things I say will be incorrect and should be corrected,” Musk later said, during an appearance in the Oval Office. “Nobody’s going to bat a thousand.”

By early March, the State Department had announced the termination of more than eighty per cent of U.S.A.I.D. contracts and all but a few hundred of its ten thousand employees. Musk had posted on X that the agency, which was placed under the direct administration of Secretary of State Marco Rubio, was “a viper’s nest of radical-left marxists who hate America.” But it could be difficult to decipher which parts of its mission were progressive and which were conservative. On February 13th, Andrew Natsios, who had been George W. Bush’s U.S.A.I.D. administrator, testified about the cuts before the House Foreign Affairs Committee. Natsios had helped lead a faith-based foreign-aid organization, and as the agency’s administrator had increased grants to religious groups. In his testimony, he stressed that many faith-based organizations would close without U.S.A.I.D. funding. Natsios recalled, “I could see the expressions on the Republicans’ faces: ‘Wait a second. No one told us that before. Are you telling me we’re going after our base with these cuts?’ ” He told me that the night before his testimony he’d had dinner with executives from several of the largest Christian N.G.O.s. They were livid. “Ninety per cent of them are on the verge of insolvency,” he said.

The Trump Administration’s campaign against foreign assistance was widespread. On February 28th, Marocco, accompanied byDOGEofficials, staged an “emergency board meeting” outside the Inter-American Foundation, which supports civil-society organizations in Latin America and the Caribbean; Marocco announced that he was now the president and C.E.O. and moved to dissolve the organization. On March 5th, officials at the United States African Development Foundation, which invests in small businesses on the continent, managed to keepDOGEofficials from coming inside; the next day, the officials returned with U.S. marshals, entered the building, and changed the locks. The following week,DOGEofficials arrived at the United States Institute of Peace, an independent nonprofit founded by Congress which works to prevent and resolve violent conflicts around the world. U.S.I.P.’s leadership believed that the institute represented a kind of boundary on theDOGEproject—an organization funded by, but not part of, the federal government. (Although most of the institute’s board members are appointed by the President, it was established as an entity separate from the executive branch.) WhenDOGEofficials presented one of U.S.I.P.’s lawyers with a resolution firing the institute’s president, he rejected it as invalid. A few days later,DOGEreturned with the police and took over U.S.I.P.’s building. (A federal judge later ruled thatDOGE’sactions were unlawful.)

The roleDOGEemployees played in these closures was not especially technical. But they offered the White House a way to avoid potential bureaucratic obstacles. “The reality is thatDOGEhas become the instrument for carrying out the will of the President,” a senior foreign-aid official told me. “The game changer for this Administration has been its ability to use this instrument in frankly unlawful ways to carry out its will.”

BeforeDOGE, U.S.A.I.D. had played a leading role in collecting health data in poorer countries on child and maternal mortality, disease incidents, malnutrition, and access to clean water. Now the ability to gather that information—“the early-warning system for the next pandemic,” as Natsios put it—was gone. A network of aid companies had established a global supply chain for medications, antiretrovirals, and vaccines. It’s now unclear what will happen to the contracts for that system, which cost a few billion dollars a year, paid for by U.S.A.I.D. “There’s no way of doing this stuff without big contractors, because they’re worldwide contracts,” Natsios said. “No N.G.O. can fill that gap.”

DOGEofficials were encountering a simple budgetary truth: radically paring back D.E.I. and humanitarian programs didn’t save that much money. U.S.A.I.D.’s spending in the most recent fiscal year had amounted to around forty billion dollars, less than one per cent of the over-all federal budget. But Natsios emphasized that, as a result of the cuts, the U.S. would be confronted with a more challenging world. In the next two years, he expected to see increased mass migration and instability because of famine. He was, he noted, an avowedly anti-Trump Republican. “But the responsibility for this belongs to Musk,” he said. “He is the one getting away with murder.”

By mid-February, small teams ofDOGEofficials were embedded at most federal agencies. (The original executive order had called for teams of four: one team leader, one engineer, one H.R. specialist, and one attorney.) They were often not a natural fit. A conservative policy analyst who spent time in the Department of Education’s headquarters this winter told me that theDOGEteam was largely siloed off, interacting only with a couple of senior staffers, and that its members seemed particularly worried about the possibility of being doxed online. “Your standard political appointee came out of the Heritage Foundation, and has a family and works nine to five and then goes home,” the conservative analyst told me. “TheDOGEguys are completely different. They are sleeping in some corner of the building, just looking at their computers. So they’re really seen almost as these exotic animals that can’t be touched.”

Erie Meyer, the chief technologist of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, was at first cautiously optimistic aboutDOGE. A veteran of the U.S. Digital Service, she had long advocated for more efficiency in government. “I thought, At least the President will have technical people advising him,” Meyer told me. She was a political appointee from the Biden Administration; she had no illusions about her own future. In January, she worked to identify projects that might interest the incoming Administration. Meyer told me, “I basically said, ‘If you want them, here are some easy wins.’ ”

On her last day at the C.F.P.B., Meyer noticed a group of five men wandering around the executive suite; one of them was trying to open the deputy director’s office, but it required a key card. She recognized another from the news—a blond twenty-three-year-old former SpaceX intern named Luke Farritor. Meyer walked out and introduced herself. Were they looking for the printer, she asked, trying to think of an innocuous explanation for jiggling door handles in the executive offices of a government agency. No, a slightly older man, “schlumpy in that D.C. way,” as Meyer put it, told her. It turned out that he was Chris Young, theDOGEleader who’d run Musk’sPAC. He and Meyer made small talk for a minute, and then the group left.

The C.F.P.B., the brainchild of Senator Elizabeth Warren, was created by Congress in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis to protect Americans from financial manipulation. Its databases are filled with details of open investigations, including the names of whistle-blowers and their specific allegations. Meyer became increasingly worried aboutDOGE’s attempts to access the vast stores of personal and corporate data housed at the C.F.P.B. On January 31st, a longtime Treasury official named David Lebryk, who led the Bureau of the Fiscal Service, which sends out payments on behalf of government agencies, resigned after clashing withDOGEofficials over their access to the payment system. Lebryk was well regarded across the government, and his resignation reverberated. As a former Social Security official put it, “When it’s, like, ‘Oh,DOGEis trying to get in and Lebryk took a bullet to prevent it,’ that’s pretty concerning, right?”

On February 7th, Musk posted on X, “CFPB RIP.” Later that day, Russell Vought, the director of the O.M.B. and aDOGEally, sent an e-mail to C.F.P.B. staffers saying that he was assuming control of the agency. Vought, an original architect of Project 2025, has been outspoken about his desire to defund government programs and fire career civil servants. “We want the bureaucrats to be traumatically affected,” he said in a private speech in 2023. “When they wake up in the morning, we want them to not want to go to work because they are increasingly viewed as the villains.”

Vought ordered all C.F.P.B. employees to stop work; eventually, more than a thousand of them were placed on administrative leave. One of the C.F.P.B.’s leaders e-mailed Mark Paoletta, the general counsel at the O.M.B., asking if the agency could at least resume monitoring companies and “was just told no—you have no authority right now.” The union representing most of the agency’s employees sued, winning a preliminary injunction to halt the dismissals. At that point, the C.F.P.B. entered a kind of zombie state, which an enforcement attorney described as “just turning on your computer to stare at it for eight hours with nothing to do.”

The Social Security Administration was under the direction of Michelle King, a career official who had recently been elevated to acting commissioner, when theDOGErepresentatives began to arrive, in early February. First came Michael Russo, a longtime tech executive who was appointed as the S.S.A.’s chief information officer; then came a coder named Akash Bobba, who had recently graduated from U.C.-Berkeley. According to a senior S.S.A. official, Bobba arrived “sort of spilling over with laptops and cellphones belonging to other agencies he was already working with.” King and her team grew wary when Russo asked for direct access to the main Social Security data files—among them the Death Master File, on which the S.S.A. records each number holder who has died. The senior S.S.A. official said, “It just was never totally clear what Mike wanted access to the Death Master File for.”

Russo and Bobba were set up in an office, working with a small group of anti-fraud officials from the S.S.A., but Bobba had not yet received the credentials necessary to access the S.S.A.’s data files. Steve Davis, incensed, started reaching out to senior S.S.A. officials. “It was ‘S.S.A has got to be the worst agency in the whole government,’ ” the former S.S.A. official said. “ ‘There’s no reason that this hasn’t happened yet. Make it happen.’ ” Russo demanded that Bobba be allowed to visit the S.S.A.’s main data center. “There is absolutely nothing to see there—a loading dock, some security, a bunch of computers,” the former S.S.A. official said. “But their view was they didn’t trust any of the permanent staff at S.S.A., so they needed Akash to get directly in.”

On February 11th, Musk joined Trump in the Oval Office and told reporters that his team had found “crazy things” happening within the Social Security system, including benefit recipients who were a hundred and fifty years old. Employees at the S.S.A. were mystified—virtually no one who had been dead more than a month was receiving benefits, and certainly not a hundred-and-fifty-year-old. S.S.A. officials, unable to reach Musk or Davis directly, tried to explain the situation to Russo, hoping that what they said would percolate up to Musk. “What was weird about that period was everything seemed to be coming throughDOGE, rather than from the O.M.B. or from the White House, but it was almost impossible to get any information up the chain,” someone who temporarily led a government agency this winter told me. “They would never let us interface with them directly, since that was sacred. So it was like a really bad game of telephone.”

That Sunday, Musk posted a chart suggesting that there were three hundred and ninety-eight million active Social Security numbers. “Yes, there are FAR more ‘eligible’ social security numbers than there are citizens in the USA,” he wrote. “This might be the biggest fraud in history.” S.S.A. officials were peeved. A week earlier, a few of them had patiently explained to Bobba that the chart contained not the number of people receiving Social Security benefits but, rather, the total number of people without death records. When officials asked Bobba about Musk’s post, he said, “I told him everything you told me. He just tweeted it anyway.”

Meanwhile, the relationship between King and theDOGEteam had deteriorated. On February 14th, S.S.A. leadership placed Leland Dudek, a sixteen-year veteran of the S.S.A., who had been working closely withDOGE, on administrative leave. Dudek posted a defiant message on LinkedIn and spent the weekend searching for a new job. Meanwhile, Davis called another S.S.A. official. “I have the agency’s complete executive roster,” the official recalled him saying. “I’d like you to go through it with me and tell me your thoughts on who should be fired.” King resigned, and Dudek received an e-mail from an official at the Office of Personnel Management notifying him that his administrative leave was lifted and he was now in charge of the entire agency.

Dudek did not think that the S.S.A. should fightDOGEdirectly. “Elections have consequences,” he wrote in an e-mail to Social Security employees. In March, according to a recording obtained byProPublica, he urged the staff to be patient with the “DOGEkids.” But he was also committed to keeping the agency functional. TheDOGEteam wanted to lay off the S.S.A.’s probationary workers. In meetings that included representatives from the O.P.M. and the G.S.A., and congressional staffers, Dudek went through the list of potential layoffs: How many were veterans or military spouses or worked in customer-service positions? Surely, Dudek said, President Trump would not want to let those people go. The total number of cuts dwindled from what might have been fifteen hundred to less than two dozen.

Dudek wanted to keep the checks going out and limit the personnel losses. But, in doing so, he was forced to make compromises. In April, aDOGEofficial named Aram Moghaddassi, an ex-Twitter engineer who was embedded with both the S.S.A. and the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, sent Dudek a request to take away the Social Security numbers of sixty-three hundred immigrants who had been allowed to enter the country during the Biden Administration. Doing so would make it impossible for those individuals to work legally, open bank accounts and lines of credit, or access government benefits. In a separate memo, the Secretary of Homeland Security, Kristi Noem, explained that the cancellations would “prevent suspected terrorists who are here illegally” from having “privileges reserved for those with lawful status.” Dudek determined that the simplest way to make the change would be to add all the names to the Death Master File, a move he soon authorized. The former Social Security official, who by then had left the agency, told me, “This was the one truly totalitarian thing the agency was asked to do.”

In the five months sinceDOGEofficially began its operations, the scale of its projected savings has steadily dwindled. Musk revised his original promise of two trillion dollars to one trillion. In May, reporters from theFinancial Timeswent through the “wall of receipts” thatDOGEhad been posting online, which now claims a hundred and eighty billion dollars in savings. They concluded that “only a sliver of that figure can be verified.” TheTimes, which has made a series of similar findings, reported, “The group posted a claim that confused billions with millions, triple-counted the savings from a single contract and claimed credit for canceling contracts that had ended under President George W. Bush.”

DOGEhas reportedly cut more than two hundred and eighty thousand government jobs—U.S.A.I.D. and the C.F.P.B. have been effectively eliminated—and the fate of much of the rest of the bureaucracy is now in the hands of federal judges. But even ifDOGE’s accounting is taken at face value, the effort has still slashed less than three per cent of the federal budget. Zachary Liscow, a chief economist at the O.M.B. during the Biden Administration, wasn’t especially surprised by the small numbers. The total cost, including pay and benefits, of all civilian personnel across the federal government, Liscow said, is just four per cent of the budget. The entire non-defense discretionary budget amounts to about nine hundred billion dollars—one-seventh of the total. Liscow, who is now a professor at Yale Law School, said cutting government personnel is unlikely to lead to savings, since fewer people helping with oversight often allows the costs of contracts to balloon: “If, in the name of efficiency, they cut a bunch of I.R.S. employees who pay for themselves many times over, it makes you wonder what motivates them.”

The savings thatDOGEuncovered were supposed to help pay for tax cuts—one Trump operative even conceived of “DOGEchecks,” through which money would be returned to the public. But the Republican budget in Congress would now add three trillion dollars to the national debt. “It’s a lost opportunity,” Howard, the lawyer and conservative regulatory specialist, told me.DOGE“was not focussed on any vision of how to make government more efficient—just on cutting. They didn’t have any vision of duplication, or of how to create more effective operating systems. You can fire the paper pushers, but if the law says you’ve got to push this paper, and there’s no one left to push it, that’s a formula for paralysis.”

Veronique de Rugy, a leading libertarian thinker at the Mercatus Center and one of the thirty-four named authors of Project 2025, also initially supportedDOGE. But she eventually grew disillusioned with what she regarded as its almost singular focus on culture-war issues. In March, she wrote, in an essay forReason, “For all the talk about cutting government waste and fraud, the DOGE-Trump team seems mostly animated by rooting out leftist culture politics and its practitioners in Washington.” She was especially concerned by the ways in whichDOGEseemed to be expanding, rather than curtailing, the powers of the executive. “Being a libertarian right now,” she told me, “is like being punched in the face with your own ideas by a drunk teen-ager.”

Even before Musk and Trump’s blowup, some ofDOGE’s main lieutenants, including Davis, were quietly exiting. Their departures offered a reminder of the essential imbalance between the bureaucrats’ enduring stake in the structure of government and the fleeting and contingent interest of Musk’s team. After Musk’s departure, Vought, at the O.M.B., became the face of what remained ofDOGE, which made a certain amount of sense: without the new-new gloss of tech, the project would revert to a more mundane, institutional form.

What, then, wasDOGE? Part of its pitch was that it would infuse government with talent, replacing diversity hires and ineffective workers with more adept ones from the startup industry. The young embeds who moved throughout the government, whom Musk raved about during his Fox News appearances, were an embodiment of this vision. But, in the end, the quickest way forDOGEto cut the government had nothing to do with technology. Lavingia told me that, during his two months at the V.A., he came to the conclusion that there were not actually so many people sitting around doing nothing. “To be honest, it is often worse in the tech industry, where you have venture money and low interest rates,” he said. “It can be pretty inefficient.”

I asked the former S.S.A. official, who had worked closely with severalDOGEcoders, what he thought of their abilities. “In general, they were all pretty talented for their level of experience,” he said. “If we’d taken them on as junior hires, they would probably have progressed pretty quickly in a hierarchical organization.” But, by design, they existed outside the civil service, with little guidance on what to do and why. “They all seemed pretty desperate for Elon to say that they were doing good,” the former official said. “There was a lot of ‘What does E. want?’ ‘Did you see what E. said?’ ” The former official compared the situation to the science-fiction novel “Ender’s Game,” by Orson Scott Card, in which a team of children who are invited by the military to play an elaborate video game are unknowingly operating actual weapons of war.

A conservative influencer familiar withDOGEmade a similar point about Musk, saying that he’d attempted to transfer the partisanship of social media to the weights and measures of the federal government. “It’s true of a lot of people, and it’s definitely true of Elon, that you live on X and your psychology is merged with the cesspool of the modern internet,” the influencer told me. “Going in and deregulating things and cutting costs might have achieved the policy result. But he’s playing a different sport—getting people to hit him really hard and then becoming a savior to everyone who hates those people.” He added, “It’s not that the vitriol from the other side is an unfortunate side effect—it’s actually the point.”

When I spoke with Lavingia, he reflected on whatDOGEhad actually achieved. It had been blamed for mass firings and contract cancellations across the government, but, in reality, it had played the role of technological adviser to politically appointed agency heads. “There’s a lot of power that comes in that first hundred days,” Lavingia said. “ButDOGEand Elon really mostly had soft power—they didn’t have hard power.” The hard power had come from Trump; the soft power depended on Musk’s influence over him. “The premise ofDOGErequires Elon and Trump to really be aligned,” Lavingia said. “And it now seems that was kind of for show.” ♦