The word “advice” comes from two Latin words: the prefixad, which implies a movement toward something, andvīsum, “vision,” a distinctly vivid or imaginative image. To ask for advice is to reach for a person whose vision exceeds yours, for reasons supernatural (oracles, mediums), professional (doctors, lawyers), or pastoral (parents, friends). It is a curious accident of language that “advice” contains within it the etymologically unrelated word “vice,” from the Latinvitium, meaning “fault” or “sin.” Yet the accident is suggestive. Alexander Pope seized on it to warn poets away from the royal court in a 1735 satire: “And tho’ the court show vice exceeding clear / None should, by my advice, learn virtue there.” The couplet, contrasting the speaker’s good advice with more nefarious influences, reveals the danger of outsourcing one’s moral vision to others. It may expose the adviser as crude, imperious, or immoral, and leave the advisee shrouded in moral stupidity. Pope’s advice? Beware bad advice from bad people.

Of course, this takes for granted that what the advisee wants is to act virtuously. But what if she only wants the adviser to affirm her vision? Pope, clever man that he was, had a couplet for this occasion, too: “But fix’d before, and well resolv’d was he, / (As men that ask advice are wont to be).” The parentheses are an inspired touch, mimicking how an advisee’s true intentions may be concealed. The advisee who feigns receptivity lays a terrible trap; woe to the adviser who does not think to step around it. Jane Austen, who often took Pope’s advice—he was the “one infallible Pope in the world,” she claimed—choreographed an elegant series of steps around advice-giving in “Sense and Sensibility.” In a discussion with the novel’s protagonist, Elinor Dashwood, the vulgar, manipulative Lucy Steele asks if she should dissolve her secret engagement to Edward Ferrars, knowing full well that Elinor loves him:

“But will you not give me your advice, Miss Dashwood?” Lucy asked. “No,” answered Elinor, with a smile which concealed very agitated feelings, “on such a subject I certainly will not. You know very well that my opinion would have no weight with you, unless it were on the side of your wishes.”

Elinor acquits herself well, but her tact accentuates how risky advice can be. The advisee may present herself as a supplicant but end up an aggressor, demanding and scornful. The adviser may begin as a sage only to end up seeming like a fraud—or, worse, an enemy, ruthlessly opposed to the advisee’s desires.

No wonder most of us prefer to give and receive advice in private, narrowing the potential for humiliation. It requires an appetite for recognition to seek or dispense advice in public, whether in newspaper or magazine columns (“Dear Abby,” “Ask E. Jean”), on TV or radio shows or podcasts (“Dr. Phil,” “Loveline,” “We’re Here to Help”), or on online forums (Mumsnet). In this wider advice industry, opinion circulates between and in front of strangers, who become keen observers of others’ shocking revelations. When advice is delivered at a live event, as with the taping of a television show, these strangers make up an audience, as concretely present to the adviser and advisee as the two are to each other. When advice is delivered over the airwaves or in print, these strangers constitute a public—what the theorist Michael Warner, in his book “Publics and Counterpublics,” describes as a virtual relationship among an indefinite number of people, who remain unknown to one another but are united by shared routines of reading and writing, speaking and listening. To pick up a weekly magazine, like this one, and read an essay, like this, is to be part of a public, along with all of the magazine’s other, invisible readers. By paying attention to words and their circulation, one becomes a member of a group, with a shared identity.

Discover notable new fiction, nonfiction, and poetry.

More than any other genre of public speech, advice brings strangers into scenes of intimate exchange. Adviser and advisee may seem to speak only to each other (often through the veil of anonymity), but their remarks will be oriented to the spectators who can read or hear their words, conferring, as Warner writes, “general social relevance to private thought and life.” These spectators evaluate the adviser and advisees on the basis of their rhetoric and their displays of emotion—in short, the styles by which they transform one person’s secret betrayal or broken promise into an impersonal theatre of moral education. Some spectators eagerly leap into the churn, asking questions, making calls, writing letters to the editor, posting comments online. This activity expands the forum of advice-giving, pulling in more voices and points of view. Advice may feel individual, but it can also be a savagely social pleasure, and it has been so for centuries.

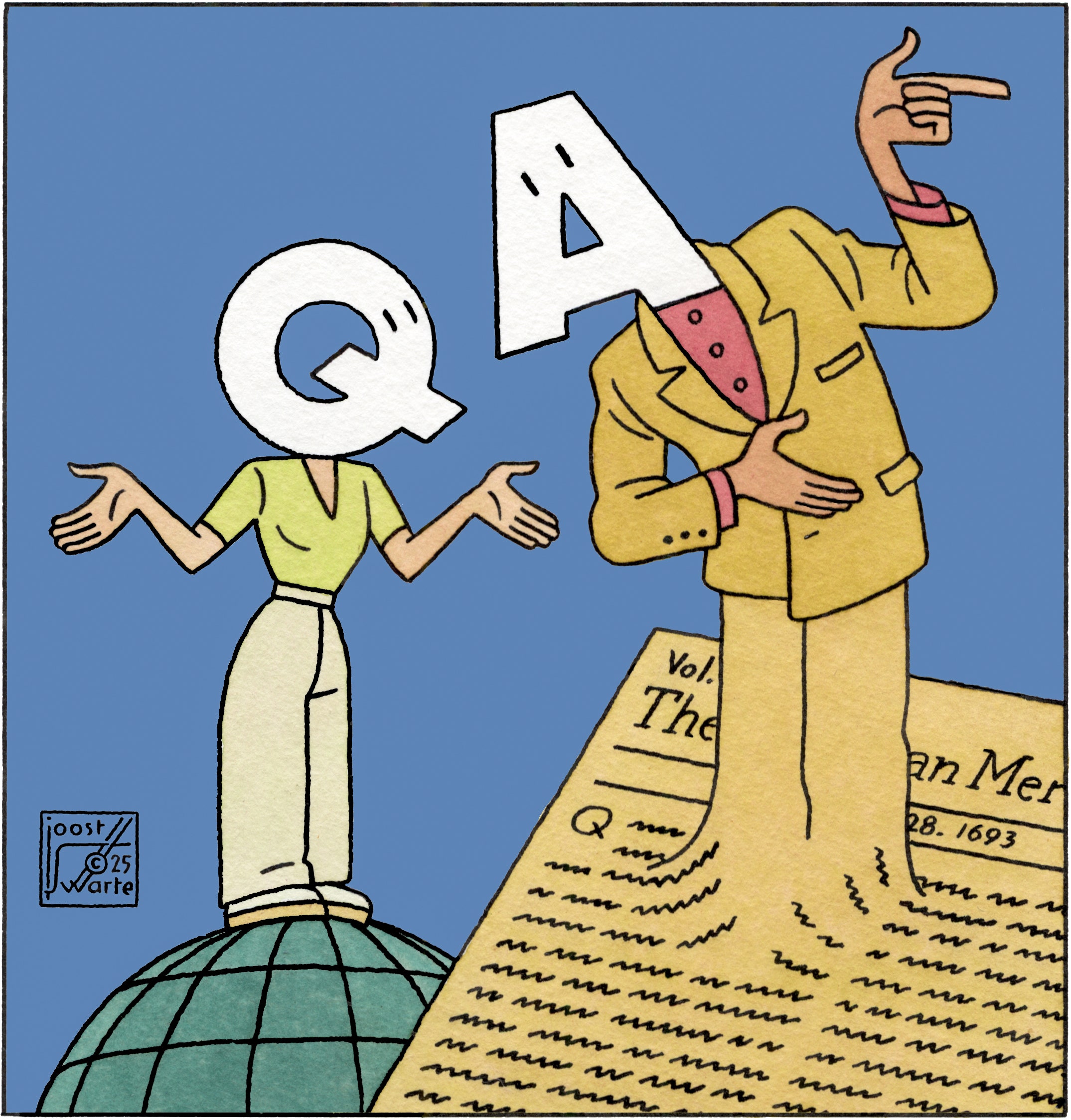

The Athenian Gazette, or Casuistical Mercury, a single-page broadsheet wholly dedicated to answering anonymous readers’ questions, first appeared in London in 1691 and was published twice a week until 1697. Mary Beth Norton’s book “‘I Humbly Beg Your Speedy Answer’: Letters on Love & Marriage from the World’s First Personal Advice Column” (Princeton) collects nearly three hundred specimens of the advice that theAthenian Mercury, as it’s usually known, offered. London was at the time Europe’s largest city, a place where crosscurrents of trade, finance, robbery, and prostitution pulled recently urbanized inhabitants into previously unimaginable relationships with strangers. In the age of print, Hamburg was the birthplace of magazine publishing, and Paris the birthplace of the literary review and the gossip rag; but restless, immoral London was where the advice column first transformed people’s private lives into object lessons for ethical behavior. The anonymity of the modern city gave rise to a distinctly modern form.

The founder of theMercurywas a Londoner named John Dunton. The reports of his contemporaries conjure a wild cross between Don Quixote and Don Draper. Descended from a long line of clergymen, he was apprenticed to a bookseller at fifteen, which seems to have decided his professional fate. He was twice married. After his first wife died, he swiftly wooed his second and celebrated his success by publishing a pamphlet titled “A Defense of a Speedy Marriage after the Death of a Good Wife”; when the second wife left him over a property dispute, he devoted himself to his beloved pet owl, Madge. He was described, in his lifetime and after, as “a Lunatick,” “a pietist and imposter,” “a poor crazed silly fellow,” and a “literary hack, with a thousand maggoty projects crowded into his bursting brain.” No doubt he was an eccentric—shady, shifting, self-enamored, and yet so imbued with a manic energy to create that he proved to be an enterprising and often brilliant publisher. He was apparently the first bookseller to publish in Boston and in Dublin, to use periodicals to advertise books, and to recognize how an advice column might organize a social space for London’s increasingly literate, upwardly mobile populace.

In an autobiography he published in 1705, “The Life and Errors of John Dunton, Citizen of London,” Dunton described theMercuryas “a Question-Project,” one of his many wondrous “Children of the Brain.” He called the letter writers “Querists,” and the respondents “Athenians,” an appellation that, he explained, was intended to “distinguish them from the rest of mankind, whom they styledBarbarians.” Rumor had it that there were twelve Athenians, like the twelve gods who presided over the agora, but in truth there were usually only three: Dunton and his two brothers-in-law, a mathematician and a clergyman. Their civilizing ambition was to answer “all the most nice and curious questions” posed by “the Ingenious of Either Sex” about “Divinity, Poetry, Metaphysicks, Physicks, Mathematicks, History, Love, Politicks, Oeconomicks.” Someone with a question could walk to the Stocks Market, in the heart of London, and deposit a letter at Smith’s Coffeehouse, where the Athenians met to collect queries and discuss which ones to answer. Outside, they would have heard the shouts of butchers, fishmongers, poultrymen, and the people Dunton had recruited—“the honest (Mercurial) women, Mrs. Baldwin, Mrs. Nutt, Mrs. Curtis, Mrs. Mallet”—to hawk copies of theMercury, for a penny apiece.

TheMercuryanswered all manner of queries: “Where was Paradise?” “Why some People love Oyl and hate Olives, and why some love Olives and hate Oyl?” But the chief concern that emerged was courtship and marriage. A browse through the broadsheets reveals how profoundly uncertain the English middling classes were about how to go about getting married and how to behave once they did. Marriage, at the time theMercurywas first published, was largely unregulated. As Norton observes, “Canon law after 1604 nominally insisted that people be married by a clergyman in a church, but requirements for place and time were so restrictive that in practice they were often circumvented.” It was another sixty years before Parliament passed the Marriage Act of 1753, “An Act for the Better Preventing of Clandestine Marriage,” which stipulated where people could marry and who could perform the ceremony. In 1691, it was still perfectly common for a couple to marry by private mutual consent, or to visit one of London’s many cut-rate marriage shops, where a disgraced priest would do the honors cheaply and quickly. The acts and ordinances of Parliament provided no guidance as to, say, how long a woman’s husband had to be lost at sea before she could remarry, or whether mutual consent could dissolve a marriage just as easily as it could make one. The obligations of coupledom remained unclear. So did the norms of courtship—the moral status of promises, oaths, and kisses, for instance, or how to value the love of a good man versus the money of a worse one.

Some questions to theMercuryasked for basic information. “Q.A young woman growing into years wishes to know what she shall do to get her a good husband? A.We answer briefly: go to the colonies.” Others were abstract. “Q.Are most matches in this age made for money? A. Both in this age and in all others.” But many Querists spun stories of longing and woe for the Athenians:

Q.I have heard a young lady make such lamentation for want of a husband that would grieve a heart of marble. She has neither father nor mother, but lives with an old miserly uncle, who will not permit any to court the poor creature, hoping in a little time to make himself master of her fortune, which is very considerable. She is to be disposed as her uncle thinks fit or else not to have one farthing. This poor husbandless young creature would be extremely obliged to you for your advice and discretion.

A. Either this poor compassionable lady must try if she can find any romantic knight of a good fortune, who . . . will take her for better or worse, without the encumbrance of a fortune. Or else they must try to be too cunning for the old fellow and trick him into a consent. Or she must patiently . . . live as merry as she can in her sad circumstances, for it is possible she may outlive her good uncle and possess his estate instead of his swallowing hers.

Q.A gentleman that has been married for several years has lately fallen in love with a young gentlewoman so passionately that he says it’s death for him not to see her. . . . However, she thinks it not a good idea to keep him company and desires your thoughts and advice upon it.

A. He may fall in lust, but in love he cannot, being himself married. Every look with such an irregular desire is in our Savior’s opinion a virtual adultery. . . . Our advice therefore is to all that are in such circumstances and temptations to stop their ears and eyes against these he-sirens.

One finds many typical figures in theMercury’sarchives: an unhappy lady and her wicked guardian; a virtuous gentlewoman and a rake; a man torn between two women, a virgin with a fortune of five hundred pounds and a widow with seven hundred; two friends courting the same lady; gaggles of spurned lovers; and, of course, variously dissatisfied husbands and wives. The Querists provided beginnings and middles for these characters’ stories. The Athenians supplied their ideal ends.

The advice they gave was shaped, above all, by their belief in the sanctity of freely and mutually agreed upon contracts. On the one hand, the Athenians believed that people had to choose whether to enter or exit relationships. Children could not be forced to marry by their parents or coerced by a particularly persistent “spark,” a suitor. On the other, once a contract was entered into willingly, it had to be honored; there could be no lying, no cheating, no nagging one’s husband, no beating one’s wife, and no leaving a marriage simply because one fell in love with a wealthier or more pleasant person. The Athenians wrote endings that were the stuff of realism, not romance. One can hear the mockery in their courtly suggestion to the Querist above that the lady find a “knight of a good fortune.” They imagined themselves as counselling a stubbornly sentimental public, who would bristle at their urging of caution and patience, and at their refusal to affirm love as an amnesiac that loosed lovers from their prior bonds.

What remains delightful about theMercuryis the style in which it addresses this resistant public: its little musings and long digressions; its carefree references to Ovid and Shakespeare; its soft, sympathetic appeals to its female readers; its deprecation of their husbands; and its coy solicitation of the lovelorn, who were encouraged to place ads for husbands or to chastise cruel suitors by showing them answers to questions in theMercury. The convergence of reason and gallantry, of irony and affection, struck a teasing tone. TheMercurymay have made the case for thoughtful commitment, but it made it in the voice of the flirt. One suspects that the Athenians picked letters that allowed them to be playful and seductive, arousing readers’ curiosity about who was giving the advice. “Whether the authors of this Athenian Mercury are not Bachelors, they speak so obligingly of the Fair Sex?” demanded one Querist. This was not a request for advice. It was a come-on: Babe, are you single? Elsewhere, such advances were swiftly shut down. Question: “Would the Athenians . . . make singular good husbands?” Answer: “The surest way to resolve the query is to ask their wives.”

Like giving advice, flirtation is a practice of persuasion. It depends on attracting attention, then regularly renewing it. Flirtation must always feel fresh, or it will feel awkward, desperate. By 1695, theMercury’svoice seemed to falter. The Querists repeated questions. The Athenians wrote shorter, more solemn answers, as if they wanted to install “a professor” in everyone’s head, as Daniel Defoe complained when launching his own Question-Project, “Advice from the Scandal Club,” in 1704. The tension between theMercury’sideas about commitment and its transgressive style had slackened. It started to publish poetry and essays instead of advice. But, like all industrious publishers, Dunton had broader ambitions: to seed new publics for his writing. He produced supplemental book reviews, bound the broadsheets into books, sold subscriptions to coffeehouses, and experimented with spinoffs that addressed more specific publics (theLadies Mercury) or varied the style of the answers (thePoetical Mercury, theDoggerel Mercury). He wrote epistolary novels set in the extendedMercuryuniverse—such as “The Secret Letters of Platonic Courtship between the Athenian Society and the most Ingenious Ladies in the Three Kingdoms”—and promoted them in the paper. By the time theMercuryceased publication, Dunton already had a vision for an advice industry.

In the history of the advice column, one can glimpse the history of what can be said in public, and by whom. As literacy expanded to new social strata, and new periodicals circulated among increasingly diverse publics, what letter writers could divulge and columnists could discuss changed. What could not be divulged was sometimes still expressed, through various styles of discretion. “It has been my misfortune to be seduced into a very great sin,” one Querist explained to the Athenians; Norton suggests that his refusal to name his “very great sin” meant that he may have been referring to either gay sex or an illicit affair.

The advice column’s regulation of sex and sexuality meant that it found a natural home in the emerging women’s pages of eighteenth-century newspapers. By the nineteenth century, it was regularly imagined as a sotto-voce conversation between friends—a single-sex space “to promote true womanhood,” as the New YorkFreeman, a leading African American weekly, boasted. When Edward Bok, the editor ofLadies’ Home Journal, started an advice column called “Side Talks with Girls,” he showed how easily men could ventriloquize women’s decorous rhetoric to discuss courtship and chastity. “When your sweetheart comes to see you, don’t be foolish enough to confine your sweetness to him alone,” the columnist proclaimed. “Have him in where all of the rest of the household are.”

Among the main strategies of discretion was anonymity, which permitted the letter writers to retain some trace of privacy and the columnist to mute aspects of his personal identity. Bok wrote the first two installments of his column under the name Ruth Ashmore, before passing the pseudonymic baton to Isabel Mallon, formerly Bab of “Bab’s Babble,” in the New YorkStar. Ann Landers was born Ruth Crowley and died Eppie Lederer. (Lederer won a contest to become Crowley’s successor in 1955.) Meanwhile, Lederer’s twin sister, Pauline Phillips, who originated the Abby of “Dear Abby,” bequeathed the legal rights to her pen name to her daughter, Jeanne Phillips. The variable readership of advice columns made a clear identity undesirable in an adviser. A columnist could become a pseudonymous celebrity, but the celebrity columnist could only be a disappointment. A friend recently showed me Martin Luther King, Jr.,’s advice column forEbony, which urged its readers to “let the man who led the Montgomery boycott lead you into happier living.” To a woman asking for help with her abusive husband, King wrote, “See if there is anything within your personality that arouses this tyrannical response.” To a boy who confessed to having sexual feelings for other boys, King encouraged him to “see a good psychiatrist.” So much for the arc of their moral universe.

Pseudonyms are still used to mediate between the columnist and her public, inviting certain kinds of letter writers and setting readers’ expectations for the style in which advice will be given. “The Ethicist,” “the Moneyist,” and “the Therapist” substitute an area of expertise for a proper name. Other pseudonyms suggest a charged affective relationship between adviser and advisee.Salon’sMr. Blue offered mocking, no-nonsense advice to the two saddest, most self-pitying creatures in the world: lovers and writers. “Dear Sugar,”Cheryl Strayed’s column forThe Rumpus, honeyed its address to soften its severest judgments: “I don’t mean to be harsh, darling.” “It was no one’s fault, darling, but it’s still on you.” Heather Havrilesky’s “Ask Polly,” which began atThe Awland then migrated toNew York, played the diminutive quality of its pen name off its author’s long, ranting sentences and potty mouth. “You know my column is three thousand words long every week, and half of those words are ‘fuck,’ right?” Havrilesky recalled asking the editor who wanted to poach her fromThe Awl. To encounter a consistent style regularly, over a period of months or years, is to develop an affinity for it, whether it flirts, lectures, insults, or coddles you, whether it imagines its reader as a sad girl or a sad sack.

As publics evolve, columnists may revise the way they address them, and these revisions may enable those publics to further shift or expand. When, in 1991, Dan Savage began an advice column, “Savage Love,” for Seattle’s alt-weeklyThe Stranger, he had readers address him with “Hey, Faggot.” Both the casualness of the greeting and the slur, reclaimed by a gay writer, marked the column as being oriented to a readership whose identity was formed in contrast to the dominant culture. The difference wasn’t in the sexual identities of the letter writers; the first installment featured straight people asking banal questions about how to pursue a crush or break a boyfriend’s Dungeons & Dragons habit. It was a difference in the framing and the tone of the advice. As Savage said in an interview, “The idea was it was going to be a joke advice column that treated straight people with the same contempt for heterosexual sex and revulsion that straight people always treated the idea of gay sex with.” So straights were regularly referred to as “breeders,” and Savage’s answers often involved insulting them. Yet it wasn’t long before his seriously bitchy, but seriously good, advice and its associated vocabulary—he coined the terms “pegging” and “monogamish”—were embraced by the dominant culture. Now the joke was on him; “straight people started responding to me,” Savage observed. In 1999, he retired the “Hey, Faggot” salutation, announcing that he had succeeded in not only reclaiming the slur but in becoming mainstream.

At its prime, “Savage Love” was syndicated in theVillage Voice, in New York; the WashingtonCity Paper, in D.C.;Westword, in Denver;City Pages, in Minneapolis; theWeekly, in San Francisco;Now, in Toronto; and many other newspapers that no longer exist. Most of the beloved advice columnists of the past two decades—Polly, Sugar, Savage—live on as thoroughly multimedia brands. They give advice through books, live events, podcasts, personal websites, and newsletters, cultivating more direct points of contact with their readers and monetizing their advice more efficiently, through subscriptions rather than salaries. Now they sit closer to the advice influencers of TikTok and Instagram, such as @erinmcgoff (“your internet big sis”) and @master.menn (“Advice for the Boys”).

Today, the most interesting digital advice forum may be the subreddit r/AmItheAsshole (AITA). Its creator, Marc Beaulac, started it in 2013, after a workplace dispute; he and his female colleagues had argued about whether he should turn down the office air-conditioning or they should wear sweaters. Beaulac wondered: Had he been an asshole? He started the subreddit to ask the question anonymously and encourage strangers to answer it plainly. Over the next few years, AITA grew into a vibrant virtual community, providing what its home page describes as “catharsis for the frustrated moral philosopher in all of us.” Its philosophers follow strict protocols. The original poster (OP) describes an interpersonal situation in which he may have behaved unethically; he may ask if it was wrong of him to, say, give away his girlfriend’s cat—he is allergic, she is unsympathetic—or rat out his best friend to a professor for plagiarism. AITA members respond to the OP and to one another, opining, debating, upvoting or downvoting other peoples’ responses, and ultimately pronouncing on the OP’s behavior: YTA (You’re the Asshole), NTA (Not the Asshole), NAH (No Assholes Here), ESH (Everyone Sucks Here).

After years of moderating the page, Beaulac remains impressed by its basic dynamic—that its members expect to retain some privacy while divulging an intimate dilemma and asking millions of strangers to weigh in. How these strangers talk is outlined by the AITA rules and its “Frequently Assed Q’s” page. The first rule, “Be Civil,” elaborates a long list of prohibitions on public speech. Posts must describe both sides of a fraught situation, but they cannot ask members to judge the ethics of breakups, sexual encounters, reproductive choices, or medical conflicts. Responses can include no direct insults (“bitch, douchebag, slut, thot, fatty, bridezilla, feminazi, incel”), no indirect insults (“you are acting like a bitch”), no censored insults (“you b!tch”), no insulting memes or emojis. There can be no taunting, no gloating, no petty spats, no bad-faith judgments, and no asking for nudes. There can be no use of A.I. to generate text. All responses must be specific to the post. They cannot invoke a user’s “broad opinion on trans people, neurodivergent people, religions, political parties, social movements, etc.” Although AITA, strictly speaking, frames its project in terms of judgment rather than counsel—“Do not ask for advice” is one of its rules—the OPs tend to describe their dilemmas with such openness and urgency that respondents give advice without being asked for it. Unsolicited advice might be a misstep between friends or spouses, but it is essential to AITA’s ideal of civility: an intensely dialogic, highly regulated style of writing, produced by and for a public of rational human beings divested of their prurient and political interests.

Implicitly, AITA style stands in opposition to the toxic disinhibition of much of the rest of the internet. Its ideal participant emerges as the antithesis of the troll, whose preferred genres of speech—railing, jeering, baiting—would have been familiar to any late-seventeenth-century reader. “Don’t feed the trolls” is excellent advice in general, but AITA recognizes that the troll is a product of the platforms that refuse to regulate a trollish style of writing. “TikTok, Twitter, FB, etc., don’t follow our rules, and, as such, should not and cannot be cited as measures of enforcement,” the page explains. There is considerable irony, then, in the question “Am I the Asshole?” If you are asking the question here, the answer is already no—not when the internet is full of actual assholes, the insulting, harassing people and bots whom other platforms have elevated to positions of influence.

Of course, not everyone who follows the letter of the law embraces its spirit. Many AITA posts are goofy, immature, or simply unbelievable. (“AITA for being pissed at my parents for taking us to Athens Georgia instead of Athens Greece?”) But there are also some that demonstrate expansive ethical deliberation among people with user names like mooseythings and ilovepancakes134. One night, I spent several hours reading thousands of responses to a 2020 post, “AITA for not letting my husband go to the funeral of the baby he conceived with his Mistress?” The OP wondered how she should handle her unfaithful husband’s request to attend his stillborn child’s funeral, organized by the affair partner—“his Mistress”—and her family:

I don’t think he should attend. He never got to meet this child and wasn’t even there at the hospital when everything happened. If this was a child he knew at all, of course my opinion would be different. But as of now, I don’t feel comfortable with him going. He (bizarrely) said maybe I should go with him. That’s a no. I obviously am not going to attend this funeral and make the woman and her whole family uncomfortable. Despite my disdain for her, I am not going to disrupt her mourning. . . . So I’m at a loss, really.

The shock among AITA readers that this stranger had entrusted them with such a painful and complex question had to be exorcised with humor before moral deliberation could begin. “Holllllllyyyyyyyyy shit Uhhhhh, I think this one is aboveReddit’s paygrade,” the most upvoted comment read. Another commenter agreed: “The last post I looked at was about putting a hat on a fucking cat. Kind of a massive jump in difficulty level.” Although these jokes may seem avoidant, they invited responses that encouraged participation by reflecting on AITA’s distinctive features as a public. “These are the situations we excel in,” a third response insisted. One could find cats in hats anywhere on the internet. Only on AITA could a woman narrate the tragic turn her life had taken and expect comprehension.

The shock also helped calibrate the style of the advice that followed. One way to understand “Holllllllyyyyyyyyy shit” is as a cautionary note: this is difficult, tread carefully. “I feel for both of you, more so than I can even express on this anonymous platform,” one respondent wrote. Another, voting No Assholes Here, added, “I wish you both can find solace.” With judgment quieted, the discussion could turn to the ethics of trust, forgiveness, and mourning, articulating what the wife owed her husband and how to honor his grief, painful though it might be for her. Some believed that he should pay his respects to the dead alone, without attending the funeral. Many more argued that if the woman had been willing to forgive her husband for the affair then she should let him bury his child.

Five years later, the people involved may have moved on. But the exchange, even in its archived form, remains remarkably alive—a careful, considered, sympathetic negotiation of distressing thoughts and feelings. Again and again, I was struck by the kindness of strangers, whoever they were. For them, giving advice was not about offering the betrayed woman a clearer vision of her life. It was a way to help her feel less alone in a world of folly and heartache. ♦

An earlier version of this article misidentified Pauline Phillips’s twin sister.