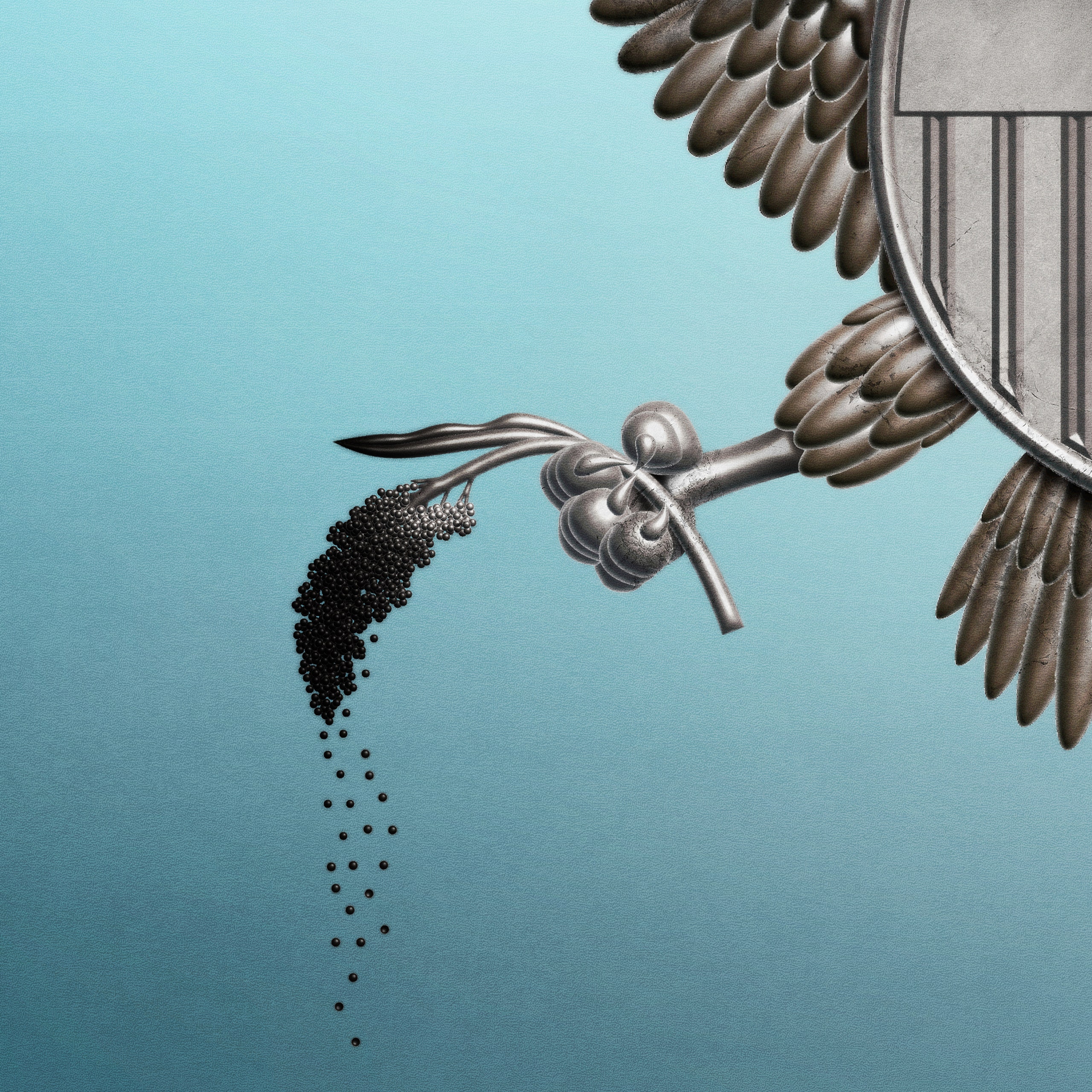

The sugarcane aphid, orMelanaphis sacchari, is an insect barely one-sixteenth of an inch long, the thickness of a penny. Its coloring ranges from beige to yellow, and it has tiny black antennas and tiny black feet. Its life span is only a few weeks, but in that time one female can produce nearly a hundred offspring, peppering sorghum plants with larvae that look like sawdust and suck nutrients from the leaves, stunting the plants. The aphid was carried from Africa by the harmattan wind across the ocean to the Caribbean; it was detected in Florida’s sugarcane fields in the late nineteen-seventies and, in 2013, on sorghum crops farther north. By the fall harvest of 2015, colonies had been detected in seventeen American states, as far north as Illinois, infecting a significant portion of the country’s sorghum crop.

The LedeReporting and commentary on what you need to know today.

Scientists at Kansas State University, working with colleagues at Cornell and in Haiti, acquired a resistant variety of sorghum from partners in Ethiopia, and tested it against strains susceptible to the bug. Within a few years, they identified the gene that served as a protective shield against the sugarcane aphid, and shared the news in the public domain. Seed companies combined the science with other control methods, making the American sorghum crop—valued at $1.45 billion last year, $739 million of which was produced in Kansas—largely aphid-free. “And that’s why we worry less about the sugarcane aphid now,” Timothy J. Dalton, an agricultural economist who directs the Climate Resilient Cereals Innovation Lab at Kansas State, told me.

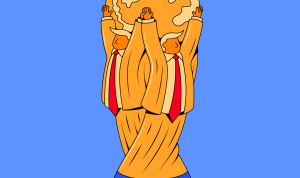

Dalton’s laboratory works in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Senegal to understand the effects of intensifying heat and drought on rice, sorghum, millet, and wheat. Until January, it was one of seventeen agricultural-innovation labs on the campuses of thirteen U.S. universities—twelve of them are land-grant schools—that were supported with tens of millions of dollars from the U.S. Agency for International Development. Four months afterElon Muskand Marco Rubio dismantledU.S.A.I.D., firing thousands of workers and cancelling eighty-three per cent of the agency’s contracts, according to Rubio’s count, Dalton’s lab is the only one left. The work, on chickpeas and poultry, vaccines and irrigation, was an important element of U.S.A.I.D.’s decades-long effort, launched by John F. Kennedy, to build influence and markets through good deeds. The laboratory projects, which started in 1978, also developed expertise and patented improvements in a competitive global agricultural economy. “By killing these programs,” Dalton said, “you’re putting America at a competitive disadvantage. You’re setting farmers up to not have the tools they need to survive in a changing world.”

The casualties include a lab at the University of Georgia that focussed on peanut-seed production and crop management, a potato-disease project at Penn State, a Washington State lab that worked on wheat, and the University of Nebraska’s research into efficient irrigation for small landholders in Africa, Asia, and Central America. The cuts also led to the elimination of an initiative at Purdue that studied how to protect food from illness-producing pathogens, at a time when the United States imports ninety-four per cent of its seafood, fifty-five per cent of its fresh fruit, and thirty-two per cent of its vegetables, according to a U.S. Food and Drug Administration report.

Health experts believe thedestructionof U.S.A.I.D. will havecatastrophic effectson millions of people overseas, owing to the termination of malaria and tuberculosis projects, maternal-health support, clean-water initiatives, and funding for food shipments, which caused the closing of a thousand community kitchens in Sudan alone. At home, the losses are more subtle, but still significant, including the cuts to the innovation labs and the Trump Administration’sattemptto eliminate Food for Peace, a government program that bought about two billion dollars’ worth of food from American farmers annually and shipped it to poor countries, a postwar projection of soft power that generated feel-good vibes.

“I hope the noble cause—spread the love, feed the needy—doesn’t go down the drain with the rest of it,” Gary White, a sorghum farmer in western Kansas, told me. A number of Kansas farmers I spoke with reminded me that Food for Peace began with a bill signed in 1954 by Dwight Eisenhower, a Kansan, and grew into an important foreign policy tool in the sixties amid the United States’ competition with the Soviet Union. “Not only are we supporting U.S. farmers, but the folks who get it are in dire need and it comes with U.S. flags stamped on the side,” Andy Hineman, who farms sorghum, corn, and wheat, in Dighton, told me. “It’s an act of diplomacy that supports our policy and supports our farmers. It’s kind of disheartening that we’re not able to do that anymore.” Or, as Isobel Coleman, who until recently was U.S.A.I.D.’s deputy administrator, put it, “I just feel real sadness that the richest country in history doesn’t feel the importance of being generous with the world’s most vulnerable people.”

A State Department official said, without offering specifics, that the Administration will “prioritize resources made and grown by our American farmers. They are the best at what they do and we look forward to partnering with them in this new phase of America First foreign funding.” Supporters ofFood for Peacein Congress are trying to salvage the program by restoring some funding and moving it under the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Dalton developed a passion for hardscrabble rural agriculture in his first job, teaching biology and chemistry in a secondary school in Kenya. After earning a Ph.D. in agricultural economics from Purdue, he studied rice farming in Côte d’Ivoire, a position that led him to travel to the sands of Mauritania and the varied climate zones of Nigeria. Later, he became an expert on dairy and berry farming, with an interest in irrigation. He has been at Kansas State since 2007, most recently working in hot and dry areas in Africa and Latin America.

Dalton is insistent that Americans will become more vulnerable without research partnerships abroad. “Insects travel around the world—diseases travel around the world,” he told me. “The work that we are doing is trying to get out ahead of these diseases and insects before they get to the United States.” He also worries about intangible costs as labs pull back or shut down. “We’re beginning to lose our advanced edge in leadership. The Chinese are investing far more money,” Dalton said. “It is about sacrificing our strategic position in global agricultural research in the same way that thecrisis with the N.I.H.will critically affect our ability to provide leadership in biomedical and biotechnology research.”

By Dalton’s count, U.S.A.I.D. channelled $1.24 billion to American universities between 1978 and 2018 for international agricultural research. He calculated that the funds yielded more than eight dollars in benefits abroad for each dollar spent, with nearly eighty per cent going to people who earned less than five dollars and fifty cents a day. He estimated that the elimination of the threat to U.S. crops from two types of aphids saved American farmers more than a billion dollars in 2025. Dalton’s lab was granted a reprieve following an appeal by the Republican senator Jerry Moran, of Kansas, to the State Department, which now runs the remnants of U.S.A.I.D., but a lab run by a colleague, the agronomist Vara Prasad, lost a fifty-million-dollar grant devoted to climate resilience.

In April, Prasad laid off most of his small staff in Kansas; more than two hundred and fifty students and scholars also lost scholarships or research funding. The largest groups were in Cambodia and Haiti, where they researched poultry and swine, peanuts and sorghum. One project studied whether border plantings of marigold or basil could deter pests from reaching fields of main food crops. “I suppose it was disbelief,” Prasad said, when I asked about his initial reaction. “This was coming from the Global Food Security Act, which has bipartisan support. It’s rooted in America First. All the extremism happening around the world? The major cause is food insecurity.” Furthermore, he said, the lessons of his lab’s work are, like Dalton’s, relevant to farmers in Kansas, where the majority of American sorghum—and a significant portion of the U.S. wheat crop—is grown.

“There is absolutely no good that can come out of the shortsighted decisions to terminate the U.S.A.I.D. program,” Vance Ehmke, a farmer who grows wheat, rye, triticale, and grain sorghum on fourteen thousand acres in western Kansas, told me. “Anything new in terms of research or technology—we quickly identify those things and put them to work on the farm.” Ehmke mentioned new developments in disease resistance and high-yield wheat varieties. “You’ve got to go on to the next thing, but, if that next thing is no longer there, you’re just progressively stuck in the past,” he said.

Bob Zeigler, a plant pathologist and the former director general of the International Rice Research Institute, spoke about what he called the “spillover benefits” of research partnerships among scientists from far-flung regions of the world. He mentioned the international collaboration that led to development of the semidwarf rice gene, which was instrumental to the Green Revolution of the nineteen-sixties. The U.S.A.I.D. funding, by developing partnerships, “prepares for the ‘Aha!’ moment,” he said, when you make that scientific breakthrough, thanks to smart minds across the globe working together. “It’s not very expensive and you buy tremendous good will. It’s heartbreaking when we see the loss of our reputation as honest brokers and reliable partners.”

For the past ten years, David Tschirley, a professor emeritus of agricultural economics at Michigan State, has run research projects in Africa and Asia, working at any given time with twenty or so faculty members and graduate students at home and countless scientists and technicians abroad. U.S.A.I.D. routed around a hundred and ninety million dollars to the university’s Food Security Group between 1983 and 2023, he said. Tschirley is also the chair of the committee that oversaw the American innovation labs funded by U.S.A.I.D., giving him a view of the researchers’ work in understanding and responding to a warming planet. Climate change, he pointed out, enables the survival and spread of foodborne pathogens, making Purdue’s work on food safety particularly valuable. Similarly, the market-resilience work performed by a lab at the University of California, Davis, offers solutions to farmers and agricultural communities that are vulnerable to intensifying weather disasters.

Beyond the immediate benefits of the labs’ work, Tschirley offered an argument that he described as “esoteric, but actually quite important,” about a long-term boost to the U.S. economy. As impoverished farmers abroad produce more food and earn more money, much of that income is spent on food for their families. “One of the big things that we see in Africa and Asia is, as the demand for food rises, the demand for grain and processed food rises even faster—and that creates huge opportunities for American companies. Those are the growth markets for us,” he told me. He added, with an eye to the America First proclamations of the Trump Administration, “The work we do is very much in the national interest. It directly helps America.” ♦