To be an informed New Yorker, or even an informed human being, you could do a lot worse than tuning into Brian Lehrer’s and Errol Louis’s respective daily broadcasts. Lehrer interviews political newsmakers and takes calls from New Yorkers with all manner of comment and complaint, as the host of “The Brian Lehrer Show,” which airs weekdays at 10A.M.on WNYC, and Louis takes the evening shift, as the host of “Inside City Hall,” a political show that airs at 7P.M.on the local cable channel NY1. Lehrer and Louis take the pulse of the city, playing the roles of municipal policy analyst, therapist, and philosopher—sometimes all three in the course of one episode. Both have engendered a loyalty in their audiences which verges on the religious. “I’ve said on air, Errol Louis is the single best reason to still have cable,” Lehrer said recently.

The pair first met decades ago, when a thirtysomething Louis appeared on Lehrer’s show (then called “On the Line”) to discuss his work running the Central Brooklyn Federal Credit Union, a community bank in Bedford-Stuyvesant, which tried to support low-income residents in a neighborhood where capital was hard to come by. “My one serious detour from journalism after college,” Louis, who also writes a local politics column forNew Yorkmagazine, now calls it. Back then, Lehrer’s show was already a pillar of the city’s local media, listened to by yuppies and yippies and youse guys alike. “You would get in a cab, and maybe thirty, fifty per cent of the time, they would be listening to Brian,” Louis said, sitting beside Lehrer at a restaurant in Chelsea. Lehrer nodded serenely. “We love our cabdrivers,” he said.

Lehrer and Louis are a natural double act, Louis’s assertive bluntness contrasting nicely with Lehrer’s dead-air calm. In the early two-thousands, when Louis was a reporter at the New YorkSun, he started filling in for Lehrer during Lehrer’s summer vacations. “Wayne Barrett would always give him shit about that,” Louis said, referring to the legendary investigative reporter at theVillage Voice. “Because amazing stories would break while he was away, and he actually put himself in a place where you could not reach him. It was a real vacation.” Lehrer rolled his eyes. He has been broadcasting nearly every weekday since 1989. “When my kids were growing up, we would take two full weeks in August,” he said. “Only in the United States would this be considered an unusually long break.”

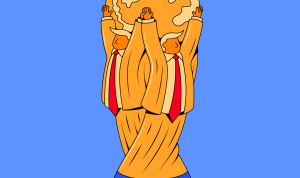

On Thursday, June 12th, Lehrer and Louis, along with Katie Honan, a reporter atThe City, will moderate a debate between seven of the leading candidates running in the 2025 New York City Democratic mayoral primary. The second of two debates includes Andrew Cuomo, the disgraced former governor and mayoral front-runner, who will appear side by side with Zohran Mamdani, the thirty-three-year-old democratic-socialist assemblyman who has solidified his hold on second place in the polls. Most of the other candidates who will appear onstage—the current city comptroller, Brad Lander; the former city comptroller Scott Stringer; Adrienne Adams, the speaker of the City Council; and Zellnor Myrie, a progressive state senator representing a swath of central Brooklyn—boast long experience in local government, and have detailed policy plans on issues including housing, policing, and mass transit. One candidate, the businessman Whitney Tilson, who ran a hedge fund after helping found Teach for America, is seeking public office for the first time.

At the first televised debate, this past Wednesday, the non-Cuomo candidates spent much of the time criticizing the front-runner’s record and rhetoric (Mamdani suggested he was a stooge for his corporate backers), trying to bait him into a gaffe (Adrienne Adams was incredulous that Cuomo had no personal regrets in his political career), or back him into a corner (Michael Blake, a former state assemblyman, pressed him on whether he’d once acknowledged the validity of arguments for defunding the police). But with so many people onstage, it was hard to sustain any theme or point for more than a few seconds. Cuomo endured the attacks with the good cheer of a man sitting in the dentist’s chair. The challenge for Lehrer, Louis, and Honan is to draw the candidates out further, to lay down markers of policy and temperament to help New Yorkers fill out their ranked-choice ballots by June 24th.

A few days ago, I met Lehrer and Louis for lunch to discuss the state of local news in the largest city in the country, Eric Adams’s adversarial relationship with the local press, and what’s going on with Juan Soto. Thursday’s debate will take place at John Jay College, and will air on NY1, C-SPAN, and WNYC, and in Spanish on Spectrum Noticias. (TheSpanishandEnglishbroadcasts will also stream on YouTube). Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

There used to be this figure called the city columnist. Everybody knew who they were, and their opinion held public attention in a very particular way. Some people say the city columnist is extinct; some people say the job has morphed or evolved. I’m putting the question to you guys, because your work seems related to whatever that role used to be. What do you think happened?

LOUIS: They got a job in TV! I’m not kidding. At theDaily News, I had a column that ran twice a week, including Sunday, which was the biggest day for theDaily News. It was Jimmy Breslin’s old column. I inherited it. Breslin, Pete Hamill, Mike Daly—those guys were legendary. I thought of them as the Irish guys. You know, it’s a gig, you have to develop a personality, you have to develop a voice. You’re telling a big story, the story of a great city, in installments.

LEHRER: Personal stories of individuals.

LOUIS: Exactly. You have to go out and report these things, you’re not just going to sit there and bloviate. But you have to make it look as if you just got up one morning and said, “Oh, here’s what’s been bothering me.” There’s a lot that goes into it.

It’s also part of what changed with the business plan. The old, general-purpose daily, there were some people who only came for the sports, there were some who only came for the comics, or the horoscope, or whatever. But there were a lot of people who came for the columnists. That’s why the papers would pay a bunch of money to a Jimmy Breslin, because there were people who were going to follow him to whatever paper he went to.

LOUIS: I suppose that they have found other ways to make or lose money, depending on what it is these newspapers are up to.

New York City still has this robust group of reporters that cover City Hall and the Mayor every day, fromPolitico, thePost, theDaily News, the local television stations, etc. The current Mayor’s relationship with them is terrible. He’s started bypassing them, the City Hall reporters, in favor of talk podcasts, conservative outlets, and the remaining bits of the ethnic media that still exists in the city. Is this situation good for the Mayor?

LOUIS: The strategy took him from something like sixty-per-cent approval down to twenty-per-cent approval, to the point where he wasn’t viable as a candidate in the Democratic primary. So I think the strategy speaks for itself. I’ve told his people this is a really, really bad idea. Trying to bypass the people whose job it is to know and understand fully and deeply the different policies that you’re trying to enact? We can help you explain it. That’s literally what we want to do.

The podcasters can’t parse them?

LOUIS: No. They’re picking people who have a surface-level understanding of the policy!

LEHRER: I think it’s happening more and more over time, in most of politics, that politicians are choosing their favorite media outlets. I wonder, Errol, if you would agree that if we go back as far as either of us can go back, that each successive mayor has limited their press access more than the last one. I say that even though Bill de Blasio came on both of our shows every week. That was part of his media strategy.

LOUIS: Yep. He decided to meet with each of us once a week as a way of telling almost everybody else, “I may not meet with you at all.”

Bill de Blasio, like Eric Adams, was convinced that the press was out to get him. Bloomberg also fought with and evaded reporters. Is mutual loathing the natural state of affairs between reporters and a mayor?

LOUIS: I think to do our job properly, and by that I mean everybody in the building at City Hall, including Room Nine, there has to be some level of connection and coöperation. There has to be. There is no point in doing a press conference about, you know, what time the beaches will open on Memorial Day if nobody’s there to tell a few million people what time the beaches are going to open on Memorial Day.

This Mayor, he created a podcast that nobody listens to, a newsletter that nobody reads, and he dances around to these entertainment shows, talking to small groups of people. It’s not a reliable way to reach millions of New Yorkers who are busy and distracted. They seem to think it’s a binary thing: either reporters want to help us, or they don’t. Or they say something demonstrably untrue, like the media is just interested in getting clicks. I don’t even know what that means.

LEHRER: I might give them a little more credit than that, in the sense that there is an incentive to come out with hot takes. I kind of hear the Mayor when he says—this isn’t a quote, but this is the gist— “I could tell you that crime is ninety-nine-per-cent down, and your questions would be about, What about the other one per cent?” I get it. But that’s kind of the nature of the business. You don’t do a story about all the airplanes that landed safely.

A couple of days after this runs, you’ll be moderating a debate with the candidates. You’re going to have seven people on that stage. Can you keep all these candidates straight?

LOUIS: We’ve been talking to them all along, and NY1 has reporters assigned to each of them. I have a podcast, and I’ve done a series of individual discussions with candidates.

LEHRER: The trick is to find a way for the listeners and the viewers to feel sufficiently informed. Like Errol, we’ve invited every major candidate in the primary—which is nine—onto the show to answer my questions and listener questions. Eight of them accepted and came on. The exception is Andrew Cuomo, because that’s his campaign strategy. We’ve also started to do segments that are issue by issue. Today we did a segment on the issue of child care: Brad Lander would aim for child care for anybody from two years old, Mamdani wants to start at six weeks, Scott Stringer is emphasizing after-school. But my fear is that there’s just so much detail that people are going to get overwhelmed and not retain that much of it.

This is the second mayoral cycle in a row where New York has had a huge Democratic primary field. Why are we getting so many candidates in these races?

LOUIS: The various election reforms that have been instituted over the last decade and a half have all intentionally made it easier for people to get in, easier for people to stay in, and frankly reduced any incentive for people to drop out. In a ranked-choice voting situation, anyone can convince themselves: “I’ll make a dramatic comeback in the eighth round.” It’s a bit of a problem.

These reforms were intended to make our elections better. Have they?

LOUIS: I have disagreements with some dear friends who are prominent in the reform movement because I have pointed out that some of this is just unrealistic. For example, we decided to come here and have lunch this afternoon, right? That was a difficult enough decision, to get us all here at the same time. But imagine, if he had said, rank your choice of whether we have Indian, Chinese, pizza, vegan, or steakhouse. Put them in ranked order. Who’s got time for that? And what would be the point? I see an upside in picking, say, the top two finishers in the primary, giving us ten days to go through the process again, and then having a follow-up debate, and then another vote—like it used to be done.

LEHRER: I think you can debate ranked choice versus an old-fashioned runoff one way or the other. The real nightmare scenario we’re looking at is in the fall election, where there is not ranked-choice voting, and it’s winner take all, no matter what small percentage of the vote they get. We may be looking at a scenario where Cuomo is the Democratic Party nominee, Zohran Mamdani or Brad Lander is the Working Families Party nominee, Eric Adams is running as an Independent, and Curtis Sliwa is running as a Republican. Which way is that going to fall? I could see at least two ways that don’t elect the Democratic nominee, even in our overwhelming Democratic city. One where Cuomo, Adams, and the Working Families Party candidate could split the roughly Democratic vote, and Curtis Sliwa gets elected mayor, or Cuomo, Adams, and Sliwa split the center-to-right vote, and so Mamdani or Lander get a win with, what, twenty-eight per cent of the vote? I don’t think that’s the way to run a railroad.

Cuomo hasn’t gone on either of your programs, but he has done Bari Weiss’s podcast, Stephen A. Smith’s podcast, and the former Miami Beach mayor Philip Levine’s radio show. Why do you think he’s not engaging as much with local journalists?

LEHRER: I think it’s the classic Rose Garden strategy. He’s leading. Why take the risk of putting yourself in a public situation where you might stumble in a way that a lot of people will notice and care about? It’s not unique to Cuomo, but I think it’s the strategy that he’s been pursuing ever since the polls started to come out as much in his favor as they have.

LOUIS: You can never explain to these people, like, I didn’t spend forty years as a journalist so that I could sandbag him. I ask questions, we’ll talk, we’ll figure it out. I’m committed to a better New York—just like you, right? But you can’t even have those conversations, because when you’re in campaign season, sometimes there are strategists who see it as, All I have to do is win. I don’t care what damage I’m doing to the truth.

LOUIS: But they’re wrong about that. They’re setting themselves up for future problems. When’s the last time Andrew Cuomo was in a full-throated public debate with anyone? We’ve seen these other candidates, they are turning into pretty fast company. They’re getting to know a lot of nuances and a lot of zingers. If Andrew Cuomo at this debate thinks he’s going to just read off his campaign website and say, “Hey, I plan to hire five thousand cops”—the questions on public safety are much, much more nuanced than that. I hope he’ll be ready.

In the mayoral campaign four years ago, like this year, there are parallel debates going on between the issues of affordability and public safety. They’re both top-of-mind issues for many voters, and they have some kind of relationship to each other. But I think anyone running for mayor right now would tell you that it’s easier to get traction talking about public safety than it is talking about affordability, even if crime and public disorder are dipping, and housing costs keep going way up. What’s happening here? Why’s it easier to talk about one than the other?

LEHRER: I think for one reason, even though crime is down, crime is always a risk, and it’s just about the most concrete risk that many people experience, or at least feel. Look at the history of our victorious mayoral candidates over the decades. We may be blue New York, but we elected Rudy Giuliani twice, Michael Bloomberg three times, and each time against well-known Democrats. And we elected Eric Adams in 2021, when he was running on crime, crime, crime.

Affordability—housing—is more nuanced. There are New Yorkers who feel that there are two burning imperatives when it comes to affordable housing. One is: New York City desperately needs more affordable housing. No. 2 is: Just don’t build any near me. So it becomes a more complicated conversation, and, therefore, harder to run on.

LOUIS: There’s two sides to affordability. You can either try to lower the actual cost, or you can try to help people make more money, but both of those are big and structural and relatively difficult to get to with the powers of the mayor, so you end up with measures like, give people a free bus pass, or something like that. Which, yeah, that’s fine.

Mamdani is getting traction by pledging to freeze rent on rent-stabilized apartments. That’s a big part of how he’s become one of the only non-Cuomo candidates to get something going here. Are there ways to have a better housing debate in the city?

LOUIS: First of all, people have to show up. I moderated a mayoral forum that was put on by the New York Housing Conference in the N.Y.U. Furman Center. They had wonderful charts. They spent dozens of hours putting together every fact you could ever imagine related to this. Most of the candidates didn’t show up. That’s a problem.

You could literally try and establish the Garden of Eden in the middle of New York, and there would be people who would say, There might be snakes in the garden, you know, or there’s poisonous apples. You have to have a public discussion, and somebody has to be an adult in the conversation and say, We can’t have both, we cannot haveNIMBYand low prices. You’re going to have some really hard conversations about trade-offs, which is the whole substance of politics, which is the whole reason you have a mayor to help conduct a discussion. Which is why I think it’s especially inappropriate and galling that there are people who are saying, I’m not going to have that conversation. That sets us up for another few years of not solving the problem.

Four years ago, theTimes’editorial board endorsed former Department of Sanitation commissioner Kathryn Garcia, helping her to overcome the name-recognition problem that a lot of the candidates are dealing with this cycle. If you’re not a celebrity, it’s hard to cut through. TheTimeshas said it will no longer endorse mayoral candidates. Does the newspaper have a duty or responsibility to endorse?

LOUIS: It was a huge mistake. They decided to throw away their influence. There were generations of politicians who would take certain positions knowing, specifically, that someday they might want or need the New YorkTimes’endorsement. They were fulfilling a function, by standing for something. It’s obviously the publisher’s decision, but it’s not a very wise one, and not a responsible one. It’s going to leave the city with one less watchdog.

LEHRER: I agree. There are few enough endorsements of any kind that actually move votes. There’s a body of people in the city who trust a New YorkTimesendorsement, or at least feel significantly influenced by it. I’m sad to see it go.

Cuomo has seemed only too happy to make this election a race between him and Zohran Mamdani, who’s in second place, painting the contest as one between an experienced figure of moderation and a young, potentially dangerous radical. There’s no question democratic socialists have made their mark on New York City politics since [Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez] broke through in 2018. I’m wondering how different or not you think the left faction in the city is today from the radical factions that existed in the past.

LOUIS: The D.S.A. and Working Families Party candidates of today are nowhere near as radical as the leftists who got elected to office in N.Y.C. in past decades. In the nineteen-forties, Harlem twice elected a city councilman, Ben Davis, who was an avowed, card-carrying member of the Communist Party and ended up serving five years in prison under an anti-Communist law.

As late as the nineteen-eighties, Democrats like David Dinkins and Brooklyn congressman Major Owens routinely ran and won with support from the Democratic Socialist Organizing Committee, a predecessor organization of the D.S.A. So, technically, you could say Dinkins was the last D.S.A. mayor. The question I have for today’s D.S.A. is: “Where, exactly, is the socialism?” They function more like a liberal-leaning political club than the vanguard of revolution.

LEHRER: I’m not an expert on this history, but one thing that comes to mind is the Occupy Wall Street movement of 2011, maybe similar in philosophy to today’s D.S.A., though not as formalized and developed. In the context of mayoral politics, though, the movement was short-lived, maybe their populist message resonated with many New Yorkers who got caught in the foreclosure crisis and the Great Recession, generally, after Wall Street melted the mortgage market. And maybe that sentiment contributed to the election of Bill de Blasio, who did run explicitly on being the most progressive candidate in the crowded 2013 primary. I think that was a moment when concerns about inequality topped concerns about public safety in a mayoral-election year.

I’ve got a historical question. Peter Stuyvesant famously told the residents of New Amsterdam that he would rule over them like “a father.” Michael Bloomberg was accused of “nanny state” stuff. Andrew Cuomo, at his height during the pandemic, presented himself as a father figure, making jokes about his daughter’s boyfriend, etc. Why does New York City so often seem to seek out daddy?

LOUIS: I don’t know if I see it that way. I mean, human primates look for alpha leaders, the same way a pack of dogs finds an alpha to run behind. I think we’re just hardwired to look for leaders, and we just happen to call it democracy. So people do things that try and make themselves look like a leader. If it was silverback gorillas, they’d puff up their chest or whatever the hell those apes do. What we do, some of what good politicians do, is not always what you would think. F.D.R. was seen as the leader of the whole Western world, and couldn’t even walk. There’s ways to pull it off.

LEHRER: I agree. I don’t think it’s New Yorkers. I think it’s human nature. We are electing somebody who’s going to be the top manager, and so we want somebody who we think can preside effectively over the city and all the complicated moving parts. I think a lot of people are experiencing an internal tension about Cuomo. They know about the way that it’s widely perceived that he covered up the nursing-home deaths duringCOVID. But they also know how they felt comforted and affirmed and taken care of at a time when Trump was trying to deny the seriousness of the pandemic at all. I think that that image of him on television at the beginning—being the father figure is one of the biggest factors—is one of the biggest things in people’s minds when they think about him.

I would add: if people really do want a father figure, that might indicate a lot of people remain stuck in traditionally gendered ideas about leadership.

Before you go, what’s wrong with Juan Soto?

LEHRER: There are so many competing theories. I’ll go with the leading theory: he’s feeling the pressure of a big contract. More than the theory that his family pressured him into signing with a team that he didn’t really want to be with. But I’ll throw another theory out there: maybe he’s got a little injury and they’re hiding it, as so often happens with baseball players. But that’s baseball, Suzyn—as they say. ♦

An earlier version of this article misspelled Errol Louis’s last name, misstated when Lehrer’s show launched, and referred to Spectrum Noticias by its former name.