A newly identified brain circuit in mice may explain why we sleep longer and deeper after being sleep deprived – and lead to new treatments for sleep conditions

How does the brain encourage us to make up for sleep loss?Connect Images/Getty Images

How does the brain encourage us to make up for sleep loss?

Researchers have discovered neurons in mice that help their brains track and recover fromsleep debt. If a similar pathway exists in humans, it could improve treatments for sleep disorders and other conditions marked by sleep impairment, such asAlzheimer’s disease.

We are all familiar with sleep debt, or the gap betweenhow much sleep you needand how much you actually get. But until now, it wasn’t clear how the brain tracks sleep loss – or compels us to make up this difference.

Read moreBeyond tired: Why fatigue sets in and how to tackle it

Beyond tired: Why fatigue sets in and how to tackle it

Mark Wuat Johns Hopkins University in Maryland and his colleagues mapped brain pathways in mice that are involved in sleep by injecting a tracer into 11 brain areas known to induce sleep. The tracer, which travels from neurons receiving signals to those sending them, revealed 22 regions with connections to at least four sleep-promoting areas.

The researchers focused on a subset of 11 previously unidentified regions. Using a technique called chemogenetics, they gave mice specialised drugs that activate particular parts of their brains. They divided the mice into 11 groups of three to four individuals, activating a different area in each group.

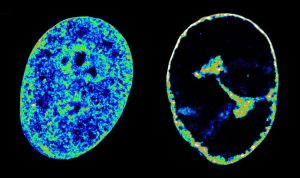

A region called the thalamic nucleus reuniens seemed to be key. When neurons in this area were stimulated, the mice experienced the greatest increase in non-rapid eye movement (REM) sleep – about twice the amount as mice that weren’t stimulated. However, it took several hours for the animals to fall asleep after stimulation, during which they seemed to prepare for rest.

Get the most essential health and fitness news in your inbox every Saturday.

“When you go to bed, you probably brush your teeth, you wash your face, you fluff your pillow or arrange your blanket and then go to sleep,” says Wu. Mice do something similar. “They kind of groom their face, they clean their whiskers and then they fluff their nest up,” he says. This suggests these neurons aren’t an on-and-off switch for sleep – instead, they induce sleepiness.

Another test also supported this idea. In six sleep-deprived mice, deactivating the thalamic nucleus reuniens brain cells made the rodents lesssleepy– they were more active and spent less time nesting than control mice. They also got 10 per cent less non-REM sleep, on average.

Other experiments showed that these neurons activate during sleep deprivation and quiet down once sleep begins.

Together, the findings suggest this brain region drives sleepiness and triggers restorative sleep after sleep loss, says Wu. Developing therapies that target these neurons could lead to new treatments for hypersomnia – a sleep disorder characterised by excessive sleepiness after rest – as well as conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, in which people don’t sleep enough.

However, it isn’t clear if the same brain circuit exists in humans, saysWilliam Giardinoat Stanford University in California. We also don’t know whether it plays a role in long-term sleep deprivation. “They’re focusing more on the short-term effects of sleep deprivation, which might not closely model humans with years and years and years of sleepless nights,” he says.

Journal referenceScienceDOI: 10.1126/science.adm8203

ScienceDOI: 10.1126/science.adm8203

Receive a weekly dose of discovery in your inbox!

We'll also keep you up to date withNew Scientistevents and special offers.